Forging New Ground: Ford Set a New Direcion for Americas

The world would have been a different place without the Model T Ford.

The world would have been a different place without the Model T Ford.

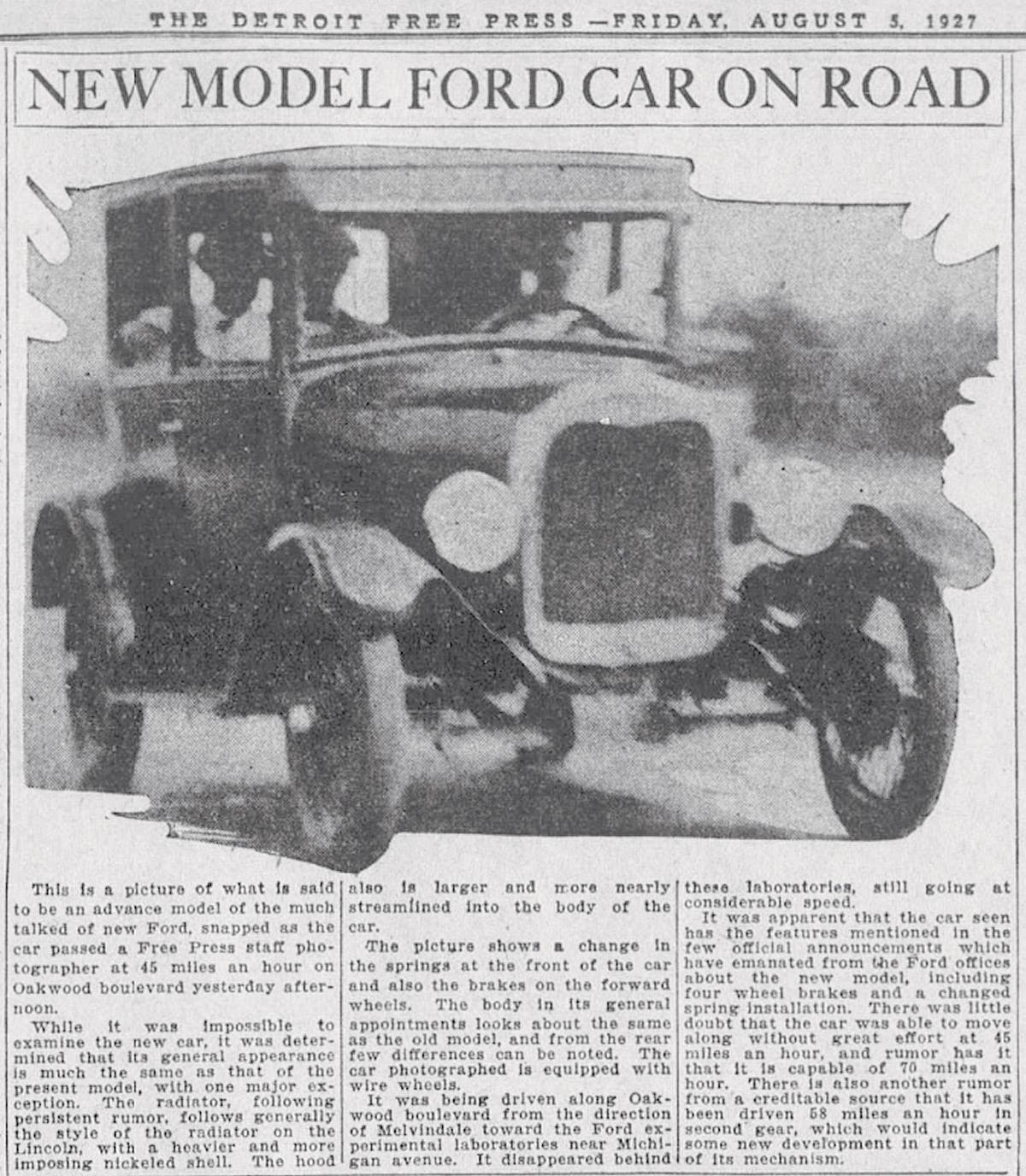

Drivers rush to work or to any number of places today, often unmindful of how their world changed in the autumn of 1908. That’s when the public was invited to consider the advantages of a car that was created by a small team of craftsmen and engineers. That group of men was led by the stubborn ideals and well-honed instincts of Henry Ford. Their creation was the Model T Ford.

The 1909 Model T Ford presented a roomy, dependable but affordable choice that was targeted to a new audience of potential buyers. Legions of new car buyers who had never thought about owning their own automobile turned to the new Ford.

The Model T set a revolution in motion and went a long way in putting North America and much of the world on wheels—an overwhelmingly number of whom had never been previoiusly able to afford an automobile. The Ford changed that thinking. It sent waves out into society that created better roads, more leisure time, new opportunities for travel and business plus much more.

Henry Ford had survived at least three failed automotive partnerships — and came close to experiencing a fourth — and he dissolved a racing venture as well. Had he not possessed an uncanny ability to gain new investors and hadn’t been held personally responsible for the financial losses like so many of the early carmakers, the Ford name might have passed into automotive history, along with other Michigan-based cars like Marvel, Paragon and Regal.

One economical, but rather stark choice for an affordable car was the go-kart-like 1903 Waltham-Orient Buckboard. It had two seats and a rear-mounted engine.

“Lovely as a burro and as useful as a pair of shoes,” was the quote used by a Ford Motor Co. executive describing the resulting Model T at a 2003 centennial celebration.

We know that Ford and his car did succeed, but what would have happened had he not?

Turning back the clock to the early automotive scene, before the Model T premiered in 1908, and consider the early years of American automobiles, in this case from 1900 to 1907.

Some vehicles had connections to bicycles. The attention given to bicycles in the 1880s and 1890s offered some hints that people wanted an affordable, practical vehicle to use for traveling beyond the prevailing horse-drawn vehicles as well as the railroads, trolley cars and steam ships.

Inventors who were entranced by the bicycle fad often turned to experimentation with small gasoline engines when they became available. And it wasn’t long before their two-wheeled test vehicles added a third or four-wheel.

Some of the most famous early automobile makers in Europe and in North America had their roots firmly planted in the bicycle world when they experimented with, then produced, early automobiles. Among the many American carmakers with bicycles in their background were Thomas Jeffery, Alexander Winton, Ransom E. Olds, the Duryea Brothers, Elmer and Edgar Apperson and their original partner, Elwood P. Haynes.

Another widespread tradition that influenced the early world of automobiles was wagon making and carriage making. It made sense that many experimental vehicles made use of available farm wagons or carriages. Attaching an engine and drive system to an existing vehicle was easier than building something from scratch. It also seemed in tune with the North American traditions of doing things for one’s self to experiment with a readily available vehicle.

By 1900, French and German makers had nearly 15 years of manufacturing. Such vehicle makers as Daimler, Benz, Renault and Panhard et Levassor already had a track record. While they had gone in the bicycle-inspired direction initially, their efforts leaned heavily toward the traditional, especially carriages. As demand grew, so did their vehicles, gaining size and weight with each year. Many North American automotive pioneers followed.

A few early automotive thinkers were not so easily swayed by the European trends. One was Ransom E. Olds, whose small curved-dash car was a best seller early in the 1900s. Olds saw a trend and wanted to make more small cars. He locked horns with Frederick Smith, president of the Olds Motor Works, who was backed by his multi-millionaire father, Samuel, the company’s chief investor.

It became an uphill struggle for Olds to argue against the prevailing wisdom, already entrenching itself, that expensive, carefully made, heavier cars, produced in low numbers, were the way to make money in the young American automobile business. Henry Ford would experience the same struggles with his partner, Alexander Malcomson.

Only a few people out of thousands could afford one of the early automobiles. For every small town or neighborhood, perhaps a wealthy businessman or doctor could afford a vehicle priced at $1,500 to $2,000 or more. For the vast majority, such an expense might be applied to a home, not a luxury. such as the automobile.

Of course, there were some alternatives. The Sears catalog offered a motorized carriage for $375 to $500, depending on adornments and modifications. Owners found a crate at the rail station and those famous words “some assembly required.” Sears soon learned offering cars was a money-losing proposition.

Farm manufacturer International Harvester followed the motorized wagon trend with a vehicle that quickly was known as the “high wheeler.” Such self-propulsion as the I-H or Sears vehicles were high on utility but very basic in terms of comfort. Styling was an afterthought, if it was even considered.

Still other companies at least attempted low-priced machines. One interesting example was the Waltham-Orient Buckboard — closer to a go-kart than to the higher priced autos with its single-cylinder, four-horse, rear-mounted engine and bicycle-style wheels. It sat on a low, flat wooden slab and offered a rudimentary wagon seat and small shroud in front of the driver and passenger. The 600-pound vehicle was powered by a 4-horsepower, one-lung engine and used a friction-disc transmission. A four-seat version also was available

One small car that “might have been,” became lost in the jungle of manufacturing takeovers. The Brush was priced right to reach more people at $500, and even made some headway in terms of reliability and durability in some national runs like the 2,636 mile Glidden Tour in 1909. Unfortunately, it was part of the failed United States Motor Co. and fell by the wayside with that failed enterprise by 1912.

Another small car candidate that bore a remarkable exterior resemblance to early Fords was the Northern Runabout, weighing in at 1,100 lbs. soaking wet and riding on a 70-inch wheelbase. The 7-horsepower Northern was made by a partnership including Henry Ford’s friend and fellow Detroit-area automotive pioneer Charles B. King.

The curved-dash (and straight dash) Olds models caught the public’s attention and probably deserved more iterations based on its success. They weighed just 1,100 lbs. and used a one-cylinder, 7-hp engine with chain drive and a planetary transmission. Between 1902 and 1904, the little Olds sold more than 11,500 copies and stood out as an example of both quantity and quality at a modest price, approximately $650.

Yet, even with the little Olds vehicles’ success story, the carrot of higher profits was too tempting to Olds Motor Works management. It was fixated on versions like the 2,100-pound Model L and 2,300 pound Model S touring cars. Those Olds Works cars were priced at $1,250 and $2,250, respectively.

It seemed everywhere one lived and everywhere one looked, someone was experimenting with a new wrinkle. Hundreds of vehicles were available in a wide range of body styles. French words once limited to carriage makers now became common in everyday conversation as people learned what a limousine, a tonneau and a coupé were. There were wooden, aluminum and pressed-steel bodies. Chain drives were as numerous as shaft-driven cars. Planetary, direct, friction and sliding-gear transmissions brought power to the wheels.

There was no uniform idea about the number or size of cylinders or even a universal fuel source, since several early cars had electric power instead of internal combustion.

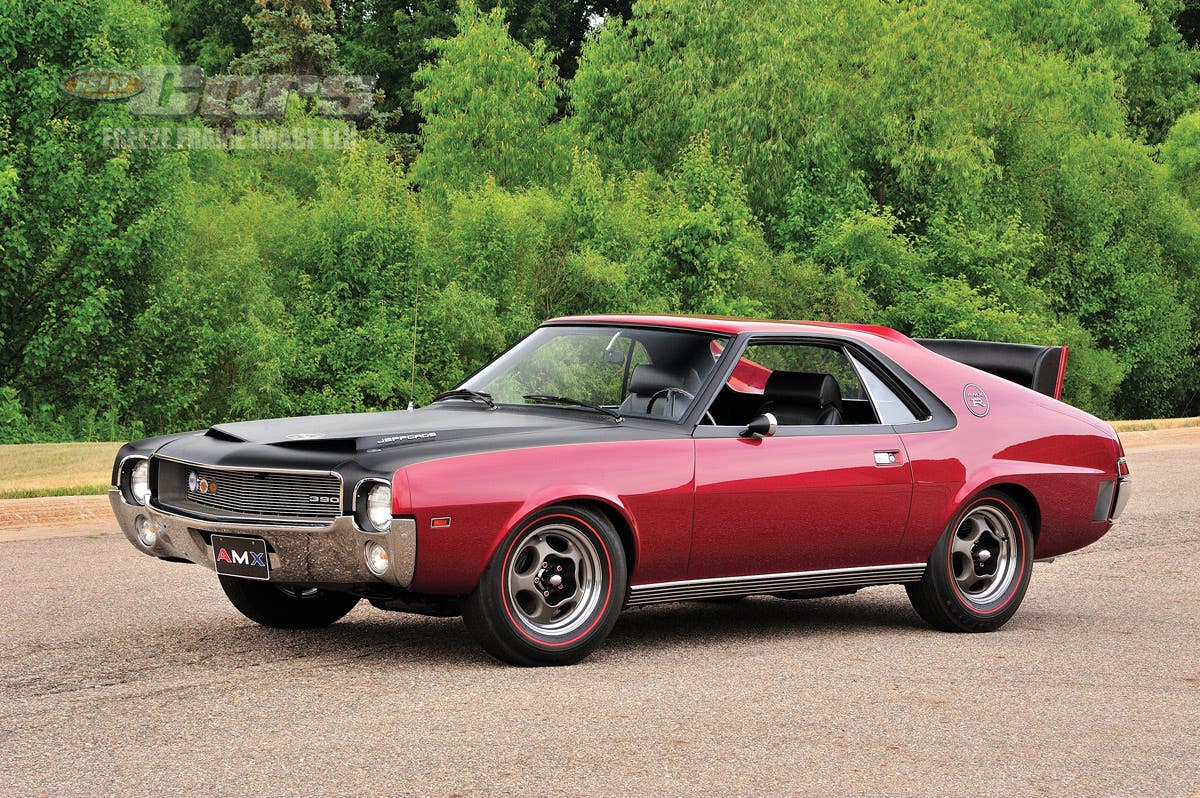

Many cars followed the Model T after its remarkable success. Perhaps the Chevrolet, Moon, Saxon, Star, Overland or some forgotten vehicle would have been the one that claimed the spotlight in the Model T’s absence.

What might have happened is lost in the shadows of history, because Henry Ford and his contemporaries produced the Model T, a car that mushroomed beyond even their expectations.

Ford and his associates were like many who dreamed of something different. They were courageous enough to think outside the box and were confident in their beliefs.

In addition, the stubborn and brash side of Henry Ford showed through when the Model T began to succeed. Rebuffed by the same organization and given the back of their hand as an “assembler” when Ford Motor Co. was in its infancy, he took on the challenge that was the stranglehold of the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers or ALAM, custodians of the Selden patent and early arbiters of who could make what vehicle and what royalties were owed them.

It was yet another way that he opened the door for his own success and for other companies to succeed making the cars and trucks they deemed appropriate.

“I will build a motor car for the great multitude,” Ford had told investor and attorney John Anderson in 1907. “It will be so low in price that no man making a good salary will be unable to own one.”

One might say the Ford team was revolutionary in 1906 and 1907 preparing its new car for the market. History tells us over and over again, they were right.

FYI:

Here’s a list of the new ideas the Ford Motor Co. offered the world or influenced with the Model T:

- Use of lightweight, vanadium steel, especially in frames.

- Mass-production methods that moved away from the carriage-style manufacturing.

- Left-hand placement of the steering wheel and steering column.

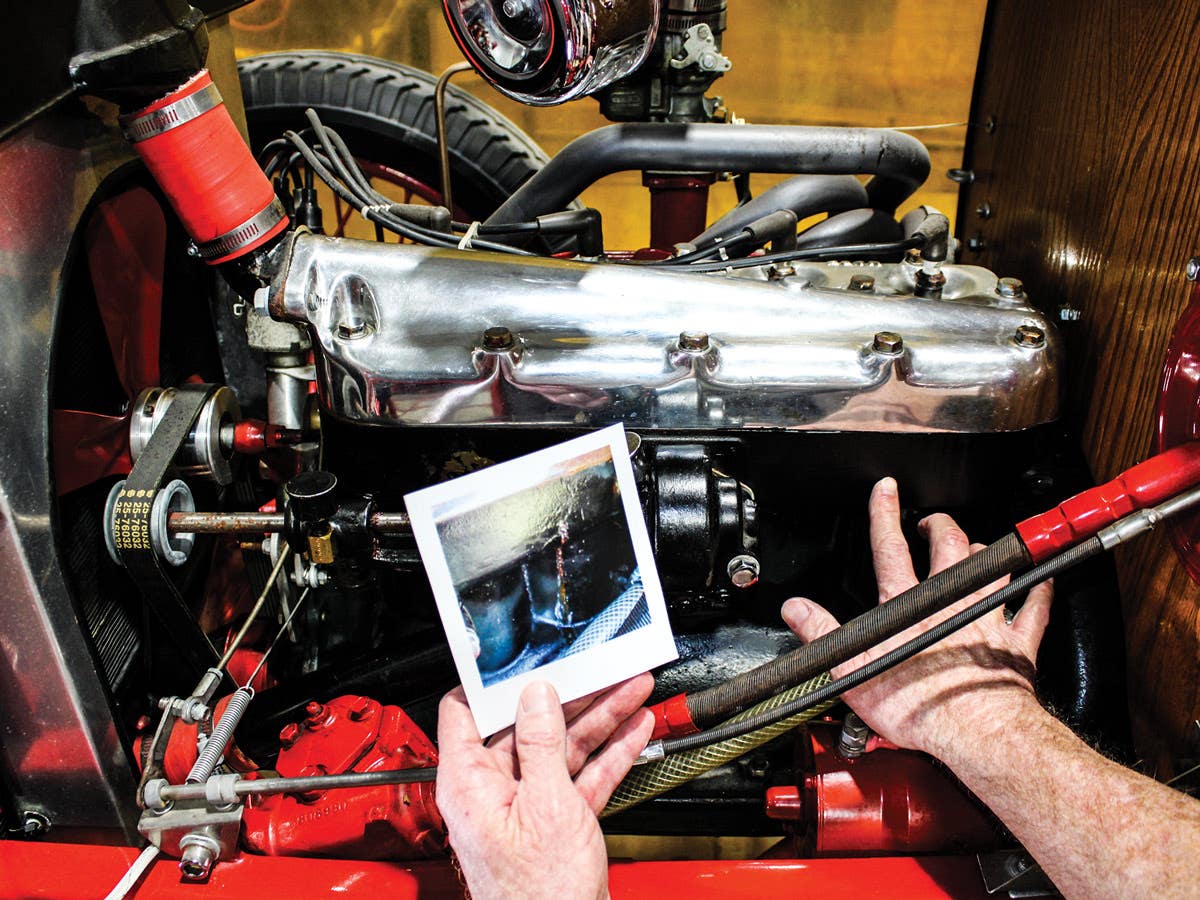

- A one-piece engine that was cast en bloc with a removable head.

- Dealer network that offered uniform parts, service and pricing.

- Uniform delivery of cars by rail.

- Mass-produced parts that encouraged availability and interchangeability.

- Regional and international automobile plants and assembly locations.

- Self-contained cars that were easy to work on and simple to operate.

- Mass-production refinements designed to lower ultimate cost per car.

- Dedicated dealers linked to a central organization.

- Self-contained mega-plant that took in raw materials and sent out a finished car.

- Company-sponsored films promoting the automobile culture, including manufacture and travel.

- Company-sponsored publications that promoted the car, its repair, traveling and work.

- Company-endorsed aftermarket sources that encouraged a limited number of sub businesses.

- High wages for work and fewer overall hours worked.

- Company-sponsored educational programs such as English language training.

- Company standards for work pay that included rules for the workplace and home.

- A recycling system that reused or collected a wide array of raw materials.

- Central company-based used and reconditioned vehicle network.

- Demand for better roads.

- International sales and marketing.

- Company-backed songs, sheet music and company-endorsed humor.

- Company-backed rebate for new car purchases.

- Increased personal mobility.

- Increased awareness of the automobile.

- Increased importance of car ownership beyond status.

- Target marketing directed to doctors, women, farmers and small business owners.

- The automobile as the versatile tool and work platform.

Learn more about the Model T Ford—or just appreciate the many advantages of these special cars with the “Legendary Model T Ford” from Krause Publications.