Full steam ahead

Old Cars Weekly archive – May 15, 2008 issue Whites turn into satisfying restoration projects for Illinois man Story by Brian Earnest; photos from George Kaforski’s collection George Kaforski doesn’t…

Old Cars Weekly archive – May 15, 2008 issue

Whites turn into satisfying restoration projects for Illinois man

Story by Brian Earnest; photos from George Kaforski’s collection

George Kaforski doesn’t try to sugar coat anything when he talks about what it’s like to own a White steamer. The cars are obscure, a little mysterious, temperamental, quirky, misunderstood and, often, downright maddening. In short, they are exactly what Kaforski was looking for after years of owning and working on other antique cars. In fact, he liked restoring his first White so much that he bought a second one – making him one of only a handful of people on the globe that owns two of the venerable steam machines. But as much as Kaforski loves them, they are certainly not for everybody.

“I don’t know if you can even find anybody you could pay to restore one of these things,” said Kaforski, a resident of Plano, Ill., “I think there is a guy in California that will restore them … But most restorers can’t do it. You’ve really got to be committed, because while you’re doing this, it’s all you think about, if you know what I mean.

“You’ve got to be one of those guys that is constantly tinkering. These cars aren’t like a Model T or something. Gas cars from that era are very dependable. You can put a Model T in a barn and get it out a year later and it’s probably gonna start and run fine. Whites don’t sit well. You can’t let them sit without running for any length of time. Stuff tends to block up.”

White is certainly associated most closely with commercial vehicles — the company still makes a line of trucks today. But from 1900-1919 the company converted from a family sewing machine business into the car-building venture and became perhaps the most accomplished steam car builder of the period. White actually outsold Stanley during its heydayfrom about 1905-’15, but eventually got out of the automobile business, leaving behind a legacy of cars that were relatively high-dollar, and certainly very high-tech, for their time period.

Very few of the 9,122 White steamers ever built survive. Whitesteamers.com, a Web site dedicated to helping White owners network with each other and trouble shoot their cars, lists only 155 cars on its roster.

“They are very nice cars, and they were very nice cars in their day,” said Kaforski. “They cost about $2,500 (for 1907 Model H, like Kaforski’s), which was a lot of money back then. Unfortunately, they also had a lot of aluminum and brass on them, which made them good cars to junk. Then, once the White company stopped supporting them, you couldn’t get parts. Ten or 20 years into the century, the steam guys were pretty much all gone and there weren’t a lot of people you could take them to. Nobody could work on them and nobody wanted them … We figure there are about 170 Whites around the world, and probably half of those are in museums.”

Kaforski has two of the ones that are most definitely not in museums, and probably won’t be anytime soon. He’s had his 1907 Model H for about 25 years and, after an eventful and challenging restoration that “took me about a year to get it looking right, and another year or two to get it running right,” Kaforski has one of the few Whites in the country that hits the roads regularly.

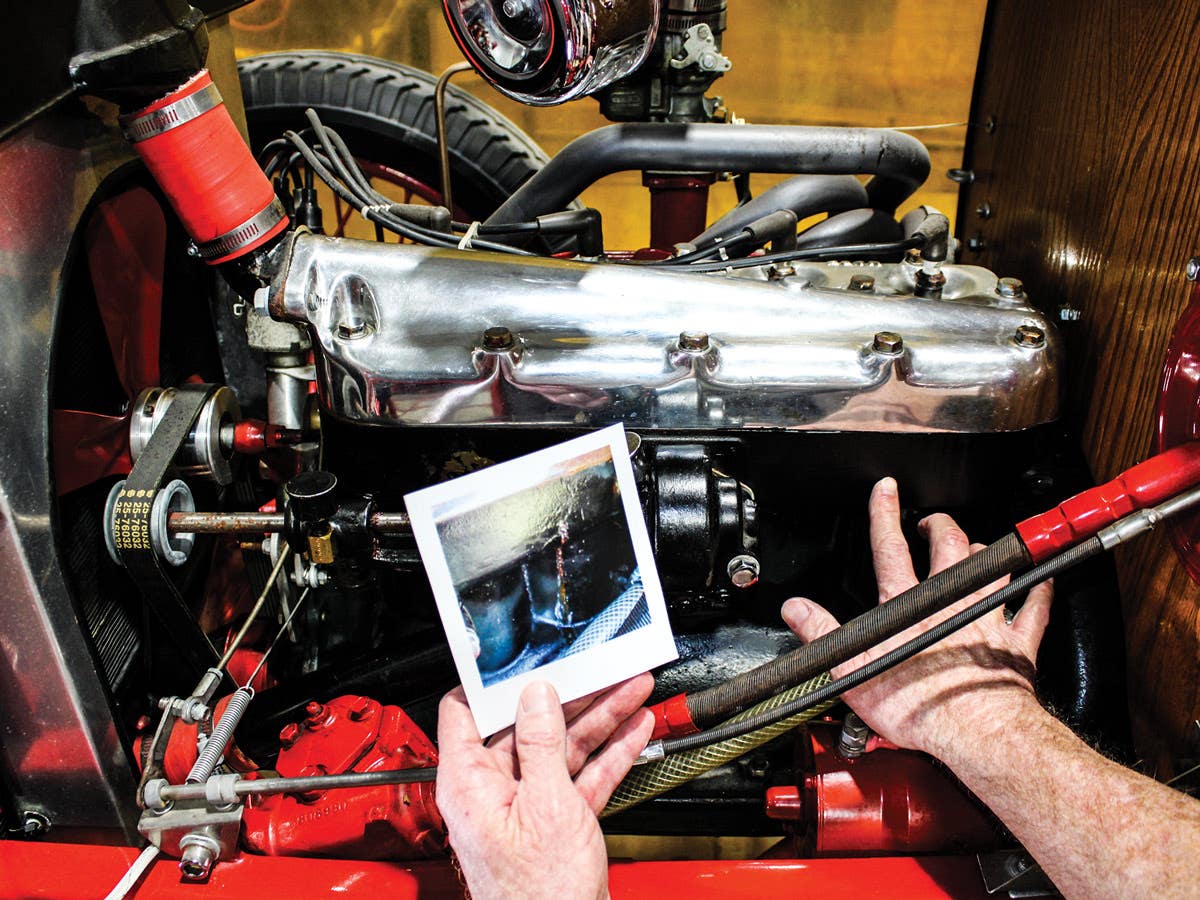

The current splendid condition of his 1907 steamer didn’t come without a lot of sweat equity and patience, however. Kaforski fabricated many of the steam parts himself, including the “monotube” generator and the condenser. Unlike the Stanley cars of the same era, the Whites had a complicated engine setup that used up steam as it was needed. The car used gas to heat the water for the steam and the entire process depended on a thermostat and a lot of know-how by the car owner, or his mechanic.

Perhaps the best explanation of how the Whites ran, comes from a 1907 manual quoted on the White Registry site:

“The White generator is radically difference from any other variety of boiler ever constructed. First, in every other known type of boiler, the water is at the bottom and the steam at the top. In the White generator, on the contrary, the water is at the top and the steam at the bottom. This fact alone is sufficient to show the unique construction of the White generator.

“This generator is composed of six to nine helical coils of 3/8” or 1/2” diameter steel tubing super-imposed upon one another. The several coils are joined in series and if the whole shouldbe unwound and straightened out, the generator would seem to be made up of a long, single piece of tubing. Below the coils is located the burner (about 23” in diameter.)The coils offer a very large heating surface so that as the products of combustion pass up between them, practically all heat is absorbed by the coils. This is the first factor which we note as explaining the excellent economy of the White system.

“The connection between the coils are so made that the water or steam, in order to pass from one coil to the one below, must be forced up to a level above the top coil and then passed down again. This feature is an important element in the construction of the generator, as it prevents water from descending by gravity and rendering the circulation down through the generator dependent entirely upon action of the pumps.

“The operation of the generator is as follows: water is pumped from the water tank, through the feed-water heater and into the upper coil and, as it is forced into the coils below, its temperature gradually rises. At some variable point, about half way down, it turns into steam (this is where the misnomer “flash” presumably crept in.)In the lower coils the steam then receives a high degree of superheat (750 degrees F) and in this condition leaves the generator and is conducted to the engine.

“As regards the safety of the system, it should be noted first of all that there is but little water and steam in the generator at any one time (about one quart) and even in the event of is “simultaneous liberation” (“explosion” is a dirty word), the effect would be inconsequential, as compared to the failure of an ordinary boiler, in which there is present not only a great volume of steam but also a large amount of water which bursts into steam the instant the pressure is reduced.

Translation: Don’t tackle a White unless you have little bit of mad scientist in you and don’t have any anger management issues. Kaforski started with his 1907 in pieces and never considered himself finished until he eventually got his machine humming reliably.

“It was just trial and error and tweaking it,” he said. “You can’t fudge on a White. It’s gotta be 100 percent right, or it won’t work right. A Model T will run down the road on two cylinders, but if anything is minutely wrong, a White won’t run. But when you get it running right, it’s really a nice car. It’s like a big old golf cart. It’s really quiet, and all you have to do, once you get it fired up and running, is just open up the throttle.”

Kaforski’s 1907 Model H was one of four models offered that year by White. It was rated about at 20 horsepower and was one of just 1,130 Whites produced for ’07. Kaforski bought the car from noted White steamer authority Joe Ersland of Oklahoma. “Joe Ersland is pretty much the No. 1 guy when it comes to these cars,” said Kaforski, a retired phone company worker. “Almost every White that collectors have has come through Joe Ersland’s hands. He was buying them up long before anybody else wanted them.

“I knew Joe and he was always trying to sell me a White. I finally decided one day that, yeah, I liked these cars and I wanted one. From then on I jumped in and applied myself and tried to learn as much about them as I could.”

Kaforski is at least the fourth owner of his 1907 White. “The earliest I can track it is to 1909. It was licensed in California — Nappa Valley — to a guy by the name of Zellner. I don’t know how long he had it, but I talked to some relatives of his and he owned a Maxwell and Cadillac dealership. Why he was driving a White I’ll never know … In the ’50s a guy named Norberry had it. He had kind of like a junkyard, I guess … and eventually Joe Ersland ended up with it.”

Kaforski doesn’t know any details on the history of his 1906 White, which he recently bought from a collector in California. As was the case with his 1907 White, the 1906 is in pieces and will require a lot of the same steps — including some parts fabrication — that were needed to get its sibling in running condition.

“I’m gonna have to do everything again,” Kaforski joked. “It’s in the same shape as the ’07 was. Most people would call it a basket case.”

After further thought, Kaforski figures it wouldn’t take long for any White, in any condition, to turn into a “basket case” if its owner wasn’t on the ball.

“Starting with it in pieces is really the only way you could afford it,” he said. “If you bought a White from a collector, unless it was just right, you’d have to take it all apart and go through everything anyway. It’s like when you see these cars in museums and they’ve been there for 30 or 40 years —there’s no way they would run. You’d have to start all over with them.”

Kaforski is sure to run his 1907 regularly to avoid such issues. He has been on two tours with the car so far, but mostly confines his driving to the country roads near his home.

“I take it out around here and I like to take it to the steam threshing shows. Those guys are always real interested when the steam cars show up,” Kaforski said. “Even the Stanley guys are impressed. And let me tell you, Stanley guys are definitely not White guys.

“They are just very interesting cars.”