The Corvette was GM’s “Little” Gamble

The Corvette was risky business for General Motors when first introduced.

The Corvette was preceded by several other American sports

cars, yet became the longest-lived of all of them.

What was General Motors to do?

When the new car market tilted in favor of the buyer, sellers had to beware. No longer was there a long waiting list for a car. No longer would buyers make do with any type of car. By 1950, those days of a seller’s market made the nod toward buyers. That meant the first full decade following World War II was going to be a hot field pitting carmaker against carmaker.

Officials at GM took notice. They saw America’s rising interest in European cars. Why? Generally, those cars were sporty. Fast. Sleek and stylish, for the most part. GM began its postwar design on Cadillacs and Oldsmobile 98s in 1948, carrying the new look through the whole GM family for 1949, with the exception of a few diehards, such as long-wheelbase versions.

Good as the styling was, people realized what it was not: It was not sporty in a European manner. Nor did it pretend to be. Even so, European styling was important for the younger generation, since many servicemen (and a comparatively small number of women) were mustered out of military service soon after the war. Many had served in Europe. They had seen European cars, occasionally driving them. If they were stationed in England, they saw a variety of designs fitted to the ancient roads and narrow streets of villages.

Studebaker saw the opportunity and did something faster than GM — debuting its Raymond Loewy styling for 1952. Its cars were low and sleek, appearing aerodynamic and exciting to tire-kickers who wanted a touch of Europe with an infusion of the Good Ol’ U.S.A. However, Studebaker stuck all its hopes in one basket with the styling. It soon became evident that too many tire-kickers were not buyers, but the company was committed financially, and for a time thereafter, had to concentrate on updates.

The Crosley Hot Shot was one of America’s earliest sports cars.

Crosley had a good shot at the true sports car crowd with its Hot Shot for 1949, and offered the slightly upscale Super Sports version soon after. Barely putting out 27 hp, the little tykes were zippy and responsive, in an American way. Each received more than its share of press space as darlings among many automobile journalists. But the 1952 models were the last. Creative Mr. Crosley could no longer afford his venture into the automobile business.

“Madman” Muntz toyed with a sports car idea, blending concepts from Kurtis, Lincoln and Cadillac into the Muntz Jet for 1952. But he lacked sufficient sales outlets to make a big splash. Besides, his car was hardly small. Call it a sports car with extra hormones.

Albeit a big sports car, the Muntz Jet was built in the early

sports car idiom.

All considered, GM knew what to do. It had to have a sports car. Not just any type, mind you. This had to set a new standard, carry an aura of its own and garner good sales.

GM was far from alone in that assessment. Mogul Henry J. Kaiser of Kaiser-Frazer was convinced by his wife to conceive the Kaiser-Darrin. When the spanking baby was born for 1954, it was powdered with the glory of stylist Howard “Dutch” Darrin, often seen as the self-proclaimed darling of American-European hybrids. Besides that venture, there was the Nash-Healey combination prompted by George Mason of Nash, who dithered with European ideas.

Enough. GM knew it was time to move out front. Enter: the Corvette.

GM’s Harley Earl was a big man, especially when it came to ideas. Leave it to others to find the funds. He found the ideas, packaged them nicely and rolled them forth for the approval of the upper echelon, which generally favored the metal expressions from his team of stylists.

Earl loved two-seat dream cars, such as the famous Buick Y-Job. Lots of size, loads of space, power to boot, but only enough intended room for the driver and one passenger. That made a statement.

Americans loved it. Car buyers wanted the Earl idea of two-person extravagance, power and handling. They were ready to pay the price for all this in a small package.

In 1952, GM Styling investigated the use of fiberglass bodies. Test results were admirable. Reportedly, it cost less than a dollar per pound for the body, and GM execs could boast of its non-rusting capability, plus its tenacity to hold up during a collision. They determined that the body panels could be as much as three times the thickness of steel at only half the weight. Fiberglass bodies then appeared on GM show cars of the future. Meanwhile, GM officials watched the reaction, counted costs for production and dreamed of success.

Think about it: Success came under the Chevrolet name. That was the steak-and-potatoes brand that brought high profits for the corporation. It made sense to produce a Corvette by Chevrolet, rather than a Corvette by Buick or Oldsmobile. First off, Chevrolet could absorb any initial red ink if the venture failed. Second, GM did not want a large sports car, which meant a downsized offering for any other brand in the GM stable. Third, Pontiac might have worked, but it did not have the large dealer network of Chevrolet. Besides, Pontiac had been carrying the image of a family car for the rising businessman who wanted a little more than a Chevy. Lastly, there was no way to make the new car a Cadillac Corvette. It was unthinkable, if a small car was the intention.

When GM gave the order to march, Chevrolet General Manager Thomas Keating did just that. It was to the tune of Corvette this time, and a good tune, indeed. Catching the passion for the project, it took Chevrolet officials a scant 18 months to dance from initial sketches to production line. The first version popped off the line in 1953. By mid year, wonderman Zora Arkus-Duntov joined the GM fold. It was a good choice for him and a good decision by Chevrolet. However, the project had Harley Earl’s stamp all over it by the time “A-K” arrived.

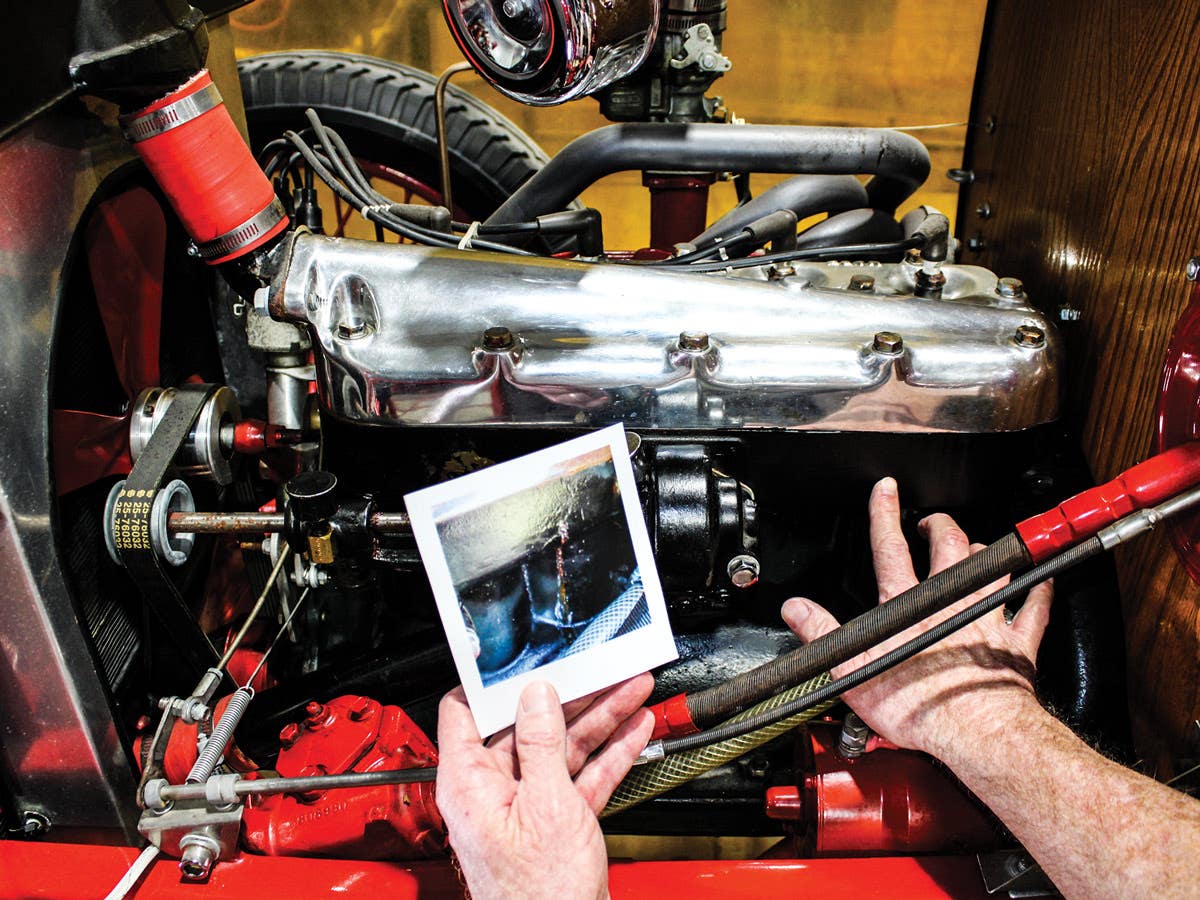

Chevrolet did not have its own V-8 at the time, so the tried-and-true Chevrolet Blue Flame stovebolt six was the engine chosen to nestle under the hood. With some tweaking, the 235-cid straight-six belted out a respectable 150 horses at 4,200 rpm. Part of the transformation involved a compression ratio increase from 7.5 :1 up to 8:1. Three Carter carburetors were mounted inline horizontally. It was challenging to keep all three synchronized — but when they were, brother, could that car go!

Sales weren’t great. But the dream continued throughout 1953, then into 1954. Upgrades resulted in the new V-8 engine for 1955. While red ink wasn’t a color that brought smiles to execs, the ultimate long-term goal was kept in focus. The model was continued.

Eventually, GM had a winner. Americans came to adore the native-born sports car. GM had made a bet, and made it right. GM had influenced the market, and only the competition spoke unfavorably.

Corvette. That’s the stuff of legend. Good for GM. Good for us.