Door Support Build Up

Story and photos by Jeff Lilly Restorations On many vehicles, particularly 1930-’49 cars and trucks, the door hinges could be extremely weak, causing the doors to sag. Not only does…

Story and photos by Jeff Lilly Restorations

On many vehicles, particularly 1930-’49 cars and trucks, the door hinges could be extremely weak, causing the doors to sag. Not only does this make the doors difficult to close, it can also chip the paint if the door overlaps the body or cab. The following steps will upgrade the door hinge area by demonstrating panel alignment, as well as the process to slice and build up the metal around door openings to achieve perfectly even gaps of 3/16 inches around the doors. No more chipping after paint!

Fat-fendered 1930s to late-’40s cars and trucks have always been in vogue and are built in many unique ways, from full-on customs to street rods with bone-stock body lines, not to mention those vehicles that have been returned to completely stock configurations. This particular project was undertaken on a 1936 Ford truck that will retain its stock lines, along with the original door hinges. In this article, we will show you how to beef up the hinge area, align the panels and get the gaps in shape. While the example vehicle is a Ford, trucks and cars from General Motors and Chrysler Corp., as well as many independents from this era, are generally of the same design and would require identical techniques.

1. The first step is to align the body as good as the factory tolerances will allow. Here, Bob loosens up all the hinge bolts and striker areas to see how close he can get to a properly fit door. The usual problems are evident, as he was only able to get it somewhat close. The factory assembly line did not have very close tolerances in the ’30s, and decades of use have not helped.

2. A close-up of the tape edges shows the door-to-cowl alignment is way off; this truck needs a lot of work. Although this area is very important, other sections of the body have to be worked first to make the process as efficient as possible. We will come back to this area later and deal with it once we see the big picture.

3. The top outside door-to-cab gap is 9/32 inches; this opening is large enough to throw a cat through, so much attention is needed.

4. The gaps are typically inconsistent, with 5/32 inches at the bottom. This is the norm. Once the perfect gap is achieved, one of the main problems is maintaining it where the hinges are attached. The hinge plates/post must be strong enough to keep the door from sliding and closing the gap once the rubber seal is installed. It is common for the gap on the hinge side to end up larger as the hinge pocket flexes from the tension caused by the fresh rubber. The door is also often pushed away.

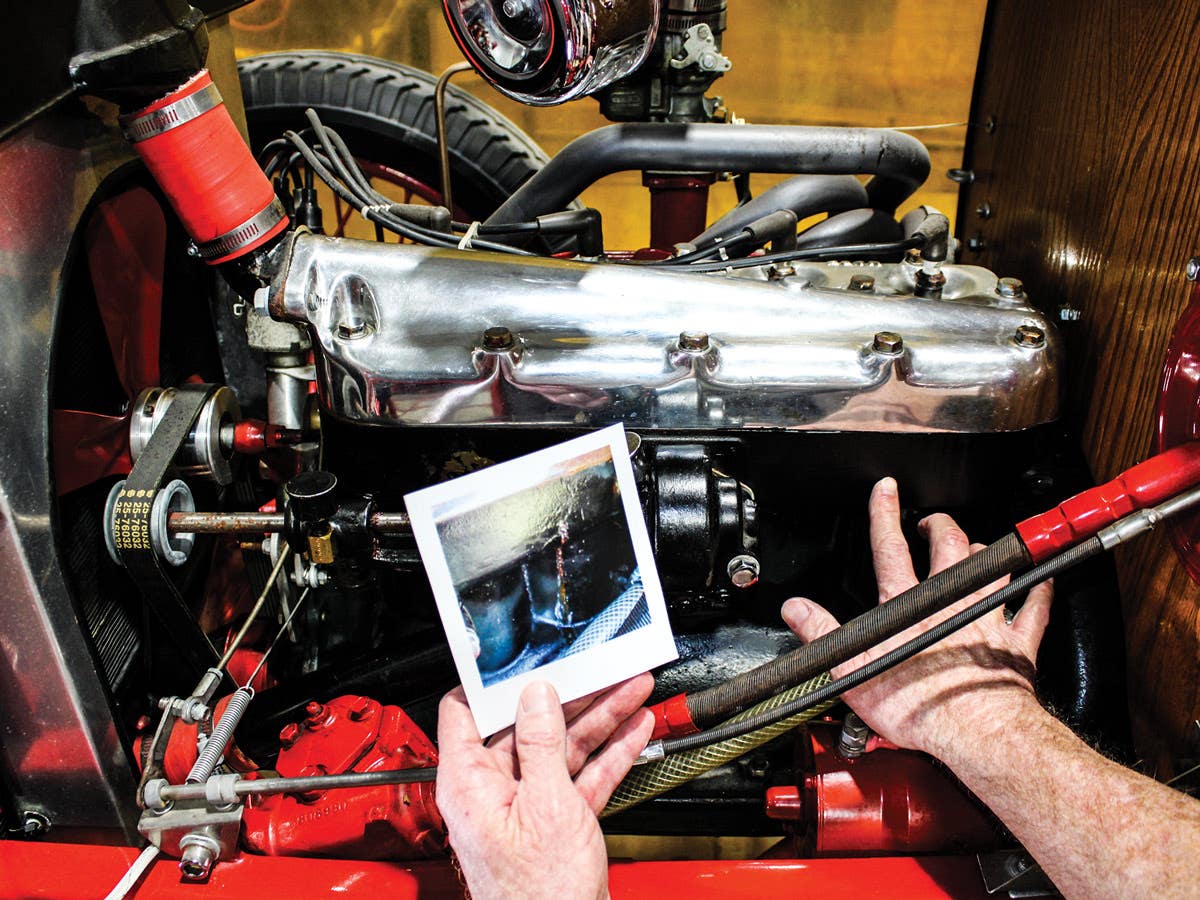

5. (Above left) The door panel is removed in this photo to show the “guilty party!” In the 1930s, this area was not beefed-up much, and it usually has a dip, as noted under the straight edge. The rivets are also part of the problem, as they weaken over the years from general use.

6. We started by cutting off the old outer sheet metal, then bolted the hinge back in place with grade 5 carriage bolts and nuts after drilling out the rivets. This inside structure is not strong enough to support the hinge by itself, so we will beef it up a bit. The metal we cut off was not even touching the hinge but merely bumping against it, which allowed the hinge to flex even more. We will add these T-braces to stiffen up the door post structure.

7. We welded in the T-plates and ground everything level. We also removed the hinge to show the nut retainers we made to enable removal of the door while working on it. It is very tight inside the door, so this aids in finger-starting the bolts and nuts when re-attaching or removing the door.

8. A new outer cover for the body of the door was made, but this time out of 16 gauge metal instead of the 20 gauge used by the factory. This allowed the space to be closed between the hinge and the original metal that was removed. It also made the space very tight with just enough clearance to slide the hinge in and out between the body metal and inner door post.

9. Here, the outer metal has been re-attached with the new door bolts, and it is all level with correct contact to the straight edge. It is now time to weld the area and re-attach the door.

10. The door is now sturdy and without flex problems, but the panels still have to be aligned as the inside lines are off. On a 1950s-or-later vehicle, the doors can be adjusted up and down at the rear by loosening the hinges. On an earlier vehicle, the only adjustment is the striker/guide system, if you do not want unsightly shims that can be seen under the hinges. Our guide plate is raising the door 1/16 inch higher than needed and we cannot adjust it any more, which is often the case. The remedy is to cut and raise the striker a little bit to allow the dovetail striker to align properly.

11. As seen here, the dovetail striker needs to be moved up. Raising just the nuts would not let it clear the factory pocket, so the complete assembly must be moved up.

12. We sliced around the perimeter, then moved it up about 1/4 inch. We then ground the welds down and reinstalled the striker. Be sure and check the alignment while you have it tacked in before fully welding it into the final position.

13. The inside lines now match.

13b. The door posts guide pins are in place and the dovetails shown in caption 11 and 12 slide precisely into place. We did, however, have to touch up the edge of the door post (red arrow), as it was so misaligned that it was hitting the edge and bending it over.

14. The hood-to-cowl gap is way off. We will start by adding a larger body mount to close up this gap. Raising the cowl will change the angle that the radiator shell aligns to the cowl, thereby closing up the hood side panels to the body cowl.

15. Just 1/4 inch more will do the trick from the math we came up with. We fabricated mounts from new chunks of red oak.

16. We have the hood, cowl and door gaps getting as close as nature will allow. We ran a string to see how all the lines matched up. As discussed in Caption 2, we can now make the proper assessment now that all the other problems have been worked out. The door and hood lines (red arrow) are dead on, but the factory’s beltline is too high on the cowl. We will use a fine line cut-off wheel and lower this section to match.

17. Note how the string now matches the length of the hood and door pretty well, except for the belt line at the cowl, which will be moved down.

18. We have done all the necessary steps in the proper order, but we still have a hood-to-cowl height problem. The ’30s were some rough years, which really takes some time to overcome.

19. Even toward the center of the hood, the straight edge shows it is more than 1/8 inch lower to the cowl. The hood is flat from front to back, so the adjustments have to take place on the cowl. Be sure the welt cord or rubber seal where the hood lays down against the cowl is installed before checking, marking or any procedures take place.

20. Where the cowl had to be sliced for a flush fit was marked on both sides.

21. As seen on the passenger side, the edge was sliced and several pie cuts were made to lower the cowl and make it match the hood. The work was done on both sides of the truck.

21b. As seen with the straight edge, the cowl and hood precisely line up.

21c. A close-up shows the beltline moved into position and ready for body work and paint.

22. Move on to the door gaps and mark back 7/32 inch, matching the gap to the body shell. This is larger than the 3/16-inch gap that is desired, but enough has to be cut in order to allow welding. After ground back to the desired 3/16 inch, enough metal thickness must be left on the edge. In this case, the middle of the door is too tight.

23. Bob uses a cut-off tool, but only cuts 1-2 inches at a time. He then tack welds it to keep the panel from splitting and separating. This keeps the panel from getting wider and retains the original thickness.

24. Bob tack welds every inch. Notice the clamp with light pressure to keep the panels from separating.

25. Only a few penetrating tacks are welded. Do not weld any more than this or the panel can be warped.

26. This close-up shows the outer panel sheet, inner panel and the third panel, which is the wrap-around section the original door skin made. Keep them tight (as mentioned in Caption 24) with no space between.

27. Tack weld, then air cool. Tack, then air cool again and repeat. Slow and smooth gets the prize.

28. Welding up door edges and cutting them back to the correct gaps takes much time when warping is not allowed. Notice the small weld beads. They are just 1/4 inch in length before they are air cooled, making sure to move around, up and down during the process. Caution: do not use a Tig welder in this step. A Tig welder takes too long to heat up the base metal around the area before a rod can be placed and melted, causing a panel to warp. A Mig welder allows instant tack welds, which then cool with the air to avoid warping.

29. Bob grinds the surface smooth, then closes the door and marks the gap exactly where he wants it to be. Again, move around some to eliminate heat build up.

30. As seen, Bob has marked the edge of the tape with a Sharpie. The tape was used to lay out the desired gap against the cab, but will now be removed.

31. Now slice right on the outside edge of the line to allow a bit of metal for fine tuning.

32. You can see the slice line in this close up. Leave just a bit remaining on the outside of the line for final fit.

33. Bob likes to finish off the gaps by metal filing for a perfect edge.

34. Here, Bob installed the door and checks it with a straight edge to show the lack of warping — just the gradual taper of the original door.

35. The area shown cleaned up, prepped and primed. The 3/16-inch gap is now dead on, and the area is ready for final preparation before paint.

Source:

Jeff Lilly Restorations LLC

11125 F.M. 1560 N

San Antonio TX 78023

210-695-5151

www.jefflilly.com

,