Alice Ramsey's cross country journey generated a lot of attention

wherever she went.

No longer lost in history, Alice Ramsey’s coast-to-coast, cross-country automobile trek from New York to California in 1909 rivals the feats of such heroines as Amelia Earhart and Nellie Bly. The National Automobile Museum, The Harrah Collection, celebrates Alice’s adventure.

The Changing Exhibits Gallery at the museum in Reno, Nevada, is honoring this adventurer with a special exhibit “On the Road With Alice Ramsey: 100 Years Ago” through April 14th, 2010.

Her amazing journey is featured in a one-of-a-kind exhibit marking the 100th anniversary of Ramsey’s drive. Ramsey, who in a day and age where little was expected of women, undertook a trip that would give pause to most modern women, or men. She drove across the nation at a time when there were few roads, few gas stations and many hazardous driving conditions.

Alice Ramsey at 22 years old, was married to attorney John Rathbone Ramsey and the mother of a two-year-old son. An experienced driver and handy mechanic, she had competed in two endurance runs in her 1908 Maxwell before undertaking the transcontinental trip.

The entire trip was the brain-child of auto salesman Carl Kelsey of the Maxwell-Briscoe Motor Company who saw a golden promotional opportunity. After noticing Alice’s driving prowess, Kelsey proposed she undertake the trip with the company furnishing the new 1909 car, paying expenses and providing assistance across the country – including pilot cars, gasoline, spare parts and tires. The plucky young lady answered, “Why not?”

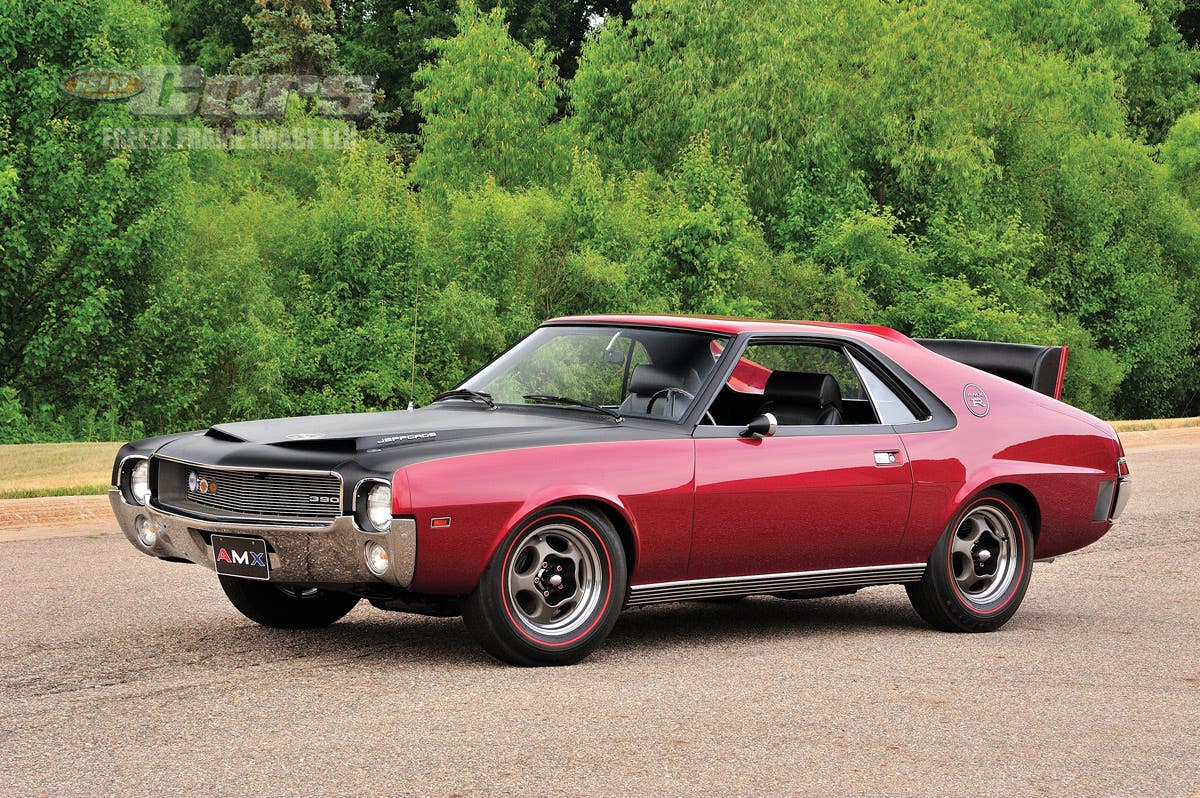

Ramsey climbed into her Maxwell Model DA, a 30-horsepower touring car with a top speed of 40 miles per hour, and drove out of the New York dealership and all the way across the country, without anything resembling an adequate road map – because there weren’t any, per se.

With her she took a 16-year-old friend, Hermine Jahns, and her husband’s sisters, Nettie Powell, age 49, and Margaret “Maggie” Atwood, a few years younger.

The right-hand drive, dark green 1909 Maxwell Model DA 30 Horsepower Touring Car, which sold for $1,750, had a four-cylinder engine that Alice described as “remarkably adequate to meet the exacting demands of that grueling endurance test.” A convertible with no side windows, the top was barely adequate to keep the passengers dry during the numerous heavy rain and hail storms. Often Ramsey and her companions suited up in full rubber protective gear, including hoods and dusters.

Ramsey took along a variety of fashionable clothing of the day. For driving and daily activities, the ladies wore cloth suits, blouses, dusters and full caps with broad brims for protection from sun and crepe de chine veils for protection from dust.

Each woman was allowed one suitcase carried on a luggage rack mounted on the back. Each packed city clothes, consisting of a dressy suit, pretty blouse and attractive shoes, a change of underwear and overnight necessities.

The exhibit at the National Automobile Museum features historical clothing similar to that worn by Ramsey and her passengers loaned from the clothing collector Sandi Larson.

Early travelers used Automobile Blue Books published by the American Automobile Association. Alice considered Blue Books as necessary as gasoline. In 1909, Blue Books were available only for areas from New York to the Missouri River, and eventually covered all of the states by 1920.

A direction from a Blue Book Alice used read: “At 11.6 miles, yellow house and barn on rt. Turn left.”

Alice and her troupe dutifully traveled 11.6 miles, but there was no yellow house. They drove on to the next corner; still no yellow house. After asking for assistance, they discovered the yellow house had been painted green by the owner who was opposed to automobiles.

Driving at night posed other problems. As Alice wrote, “After dark, objects took on an entirely different aspect” “in the eerie artificial light (of the headlamps). . .various ghostlike apparitions increased the tension of the lonely drive.”

The trip required the assistance of many ranchers and farmers as well as townspeople along the way. Horses and wagons helped pull the Maxwell out of deep mud on several occasions. Maxwell also sent along a support team.

Along the way Ramsey conquered a country with virtually no paved roads, since most passages were dirt, deeply rutted and mud packed, wagon and horse trails; hilly country that required block and tackle to continue.

In Iowa it took 13 days to navigate 360 miles of mud. Nebraska roads were so rough the rattle shook screws loose, the spring on the brake pedal snapped and the axle broke. In Wyoming roads were mere wagon and horse trails, dotted with ravines.

At one point Alice carefully descended one arroyo 60-foot deep. On the other side ascent was so gravelly and steep there was no traction, and so narrow there was no room for tacking.

Alice had to attack it head on. As she wrote in her book, Veil, Duster, and Tire Iron (1961):

“Everyone out but the driver!” Each passenger stood ready with rocks or blocks of wood to place under the rear wheels. The method was this: Give her gas in low and pull ahead a few inches. Block the wheels. Repeat this process again and again. Eventually with good power, stout and willing helpers, and plenty of time and patience, we reached the crest and were up on the plateau once more.”

A bridge had washed away over the Platte River in Wyoming. Alice had to drive on railroad tracks along a 20-foot raised embankment for ¾ of a mile. The ties were just far enough apart that if Alice stopped, the wheels would become stuck between the ties. She had to keep moving.

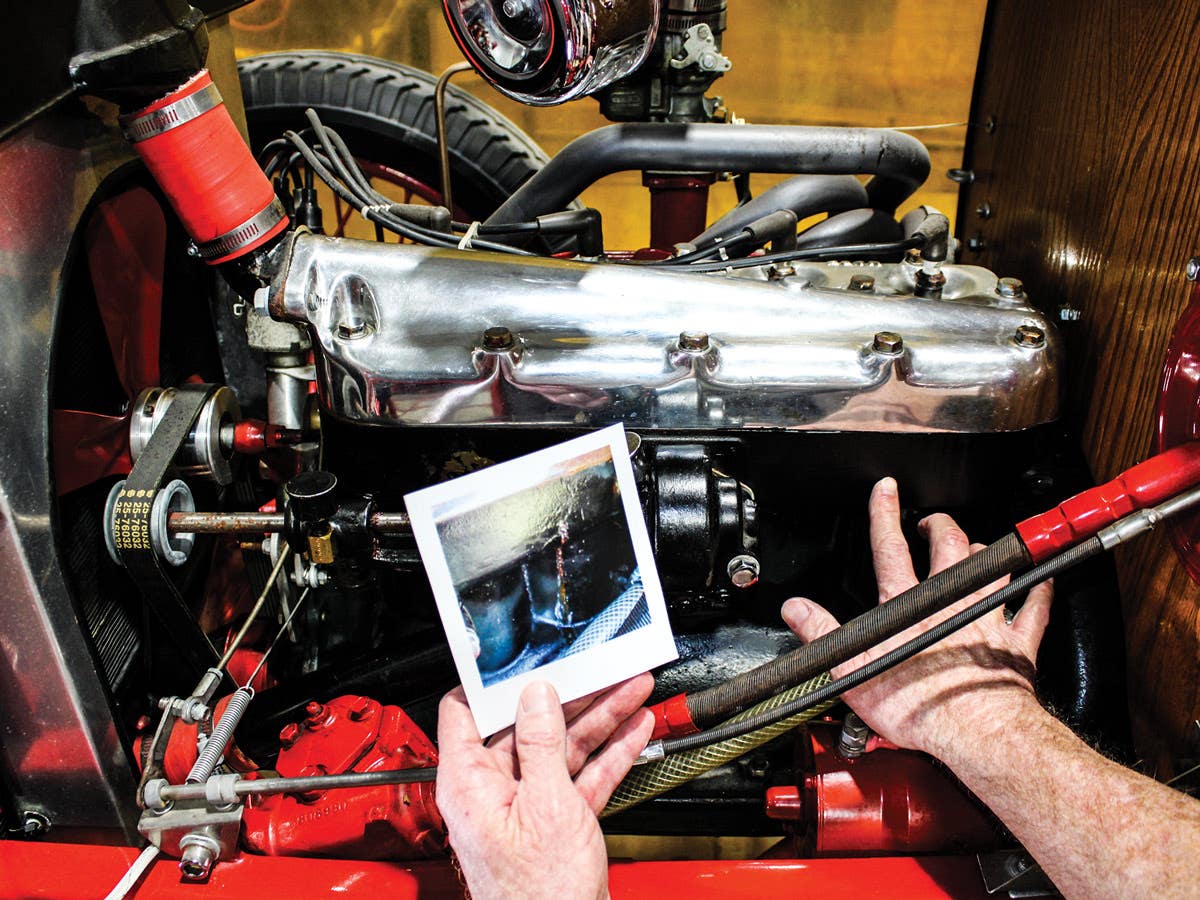

Road conditions caused several minor and some major repairs to be made to the Maxwell during the trip.

By Salt Lake City, the Maxwell’s spring bumpers and shock absorbers were in need of repair, particularly after driving on railroad tracks. Repairs included separating and oiling the spring leaves, and taking the extra precaution of wrapping them for the desert and mountain roads ahead.

Driving along a trail in barren Utah dotted with sagebrush and prairie dog holes, there was a tremendous bump as the Maxwell hit a hole and the wheels splayed out in opposite directions. The radiator hit ground. Wire was tightly wrapped around the spring and axle, and they slowly drove to a ranch with a forge.

A strip of steel was heated and, while removing the wire, the steel was bound around the spring and axle. Before the ladies could get out of Utah, the axle rolled under the car and the spring and newly forged steel strip separated while crossing a 12-foot-wide, 4-foot-deep ravine. Alice and the driver of an accompanying car removed the axle from the Maxwell by and took it to a blacksmith for repair.

Alice and companions were delighted to see the lights of Sparks, Nevada, as they rolled West because they indicated electricity and the return to civilization. It was almost midnight when they reached the Riverside Hotel in Reno. Joyous “Maxwellites” greeted them and were eager to escort them on their final lap to the Golden Gate. The next day they were sent off from Reno with cheers and good wishes.

It was a steep, sandy grade ascending the Sierra Nevada over a trail traveled by trucking wagons and horses, mules and oxen. Although it took eight hours to travel 70 miles, the ladies were awestruck by the beauty of Lake Tahoe and the glorious entrance to California.

The finish was in sight. Alice, Nettie, Maggie and Hermine arrived in San Francisco on August 7, 1909 -- 3,800 miles and 59 days after departing New York on June 9. Crowds gathered in automobiles, with horns honking, to greet the ladies.

Chinese immigrants in traditional pigtails and clothing were everywhere. Press and photographers covered the historic event with excitement. Alice’s companions remained in San Francisco for a few days of sightseeing, but Alice was anxious to return home to her husband and son. She and the Maxwell quickly boarded a Southern Pacific train heading east.

Alice’s feat reinforced the fact that cars were here to stay and proved that women were not only emerging as reliable drivers and gaining new freedom, but they were becoming buyers of automobiles and represented a new market for the auto industry. Alice Ramsey may not have been a suffragette or a woman’s libber, but she was way ahead of her time.

Milestones

The 50th Anniversary of Alice’s transcontinental journey was commemorated at the 43rd National Automobile Show in Detroit, Michigan, in October 1960 where Alice was named “Woman Motorist of the Century” by the American Automobile Association.

She was named the “First Lady of Automotive Travel” by the Automobile Manufacturers Association. She published her book on the pioneering trip in 1961.

In 2000, Alice was the first woman inducted in the Automotive Hall of Fame in Dearborn, Mich.

Alice Ramsey died September 19, 1983, at the age of 96, in Covina, California, where she had moved in 1939, five years after the passing of her husband.

If You Go

The National Automobile Museum at 10 S. Lake St. in downtown Reno is open Mon. – Sat. from 9:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. and Sun. from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Admission is $10 for adults, $8 for seniors and $4 for children age 6 to 18. Children age 5 and younger are free. Parking is free in the Museum lot. For more information, call (775) 333-9300 or visit www.automuseum.org.

[Editor's Note: Alice Ramsey was one of the first inductees into the new Buffalo Pierce Arrow Museum Hall of Fame. Ramsey was honored posthumously at a ceremony in Buffalo, N.Y. last Friday, Oct. 23. Other inductees included Emily Anderson, Seattle, who retraced Ramsey's New York City-to-San Francisco journey this spring in a 1909 Maxwell. To read about Emily's trip, go to: http://www.oldcarsweekly.com/article/alice_ramsey_coast_to_coast/]

MORE RESOURCES FOR CAR COLLECTORS FROM OLDCARSWEEKLY.COM