Car of the Week: 1933 Graham Blue Streak

A look at a streamlined trendsetter, the often-imitated 1933 Graham Blue Streak.

Amid the depths of the Great Depression, Graham was on top with the most modern-looking American car in 1932. When the little-changed 1933 models returned to the streets in 1933, Graham could boast it had “the most imitated car.” Nearly every other automaker for 1933 had copied the Graham’s sloped grille, its raked-back A pillars and low windshield, its skirted fenders and its other modern features. The look wasn’t enough to make Graham become one of the best-selling cars in the 1930s, but it was enough to turn a hot rodder into a restorer during the 2000s.

“I had been a hot rodder,” says David Anderson, owner of the featured 1933 Graham Model 64 coupe. “I was raised with Ford flatheads and in the hot rod scene. I bought a 1934 Graham and just got hooked on Grahams, and they’re so rare, you wouldn’t dare hot rod them. That’s how I became an ‘original car’ guy.

“What I have is a ’34 eight-cylinder supercharged sedan,” Anderson continued. “The interesting thing there is it was factory supercharged. They sold both non-supercharged and supercharged eights, and that is what started this whole crazy thing.”

That “crazy thing” Anderson is referring to is his impressive collection of 1932 to 1935 Graham Blue Streak models. It started with the supercharged sedan that he quickly fell in love with, and as a second-generation hot rodder, Anderson then found himself in search of a Blue Streak coupe. With the Graham Blue Streak’s overall low and sleek looks, especially as a three-window coupe, it looks custom from the factory — something rodder and restorer alike can appreciate.

“From my hot rod days, the coupe was the hot car, so I have always loved coupes and I had been chasing Graham coupes for 15 years,” Anderson said. “Grahams are so few and far between and they don’t come for sale that often, so when this thing came for sale, I bounced on it so quickly.”

The 1933 Blue Streak coupe came up for sale in 2017 a few years after its longtime owner and Anderson’s fellow Graham Owners Club International (GOCI) member David Corbin had passed away.

“I bought the car from David Corbin’s son-in-law. He passed away and his son-in-law reached out to the club, and fortunately I was on the club’s distribution list. I was immediately on the phone making the deal. There was no hesitation whatsoever.”

Anderson had known about the 1933 Blue Streak coupe for years as it had been on the GOCI’s roster of cars since the club’s founding in 1971. Early club members Andrew Whittenborn and Bill McCall shared an interest in Blue Streak models and maintained a registry of known 1932-1935 Blue Streaks since the club’s first years. Their records showed that the original owner of Anderson’s coupe drove it to the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair, then died shortly thereafter. His widow parked the car until it was spotted by gas station owner James Rohen of Evart, Mich., who drove a school bus in addition to operating his gas station. He spotted the coupe on his bus route and in 1959 inquired about the car. The widow sought $25 for the Graham coupe, but Rohen gave her $50.

During Rohen’s ownership, the car had 11,000 miles and required minor engine work. Rohen also added some non-Graham parts before selling it to an unknown owner in 1974. That unknown owner sold it to GOCI member Harry Sjaarda in the early 1980s. During next owner Joe Harvath’s time with the car, McCall noted the coupe had mileage in the 13,000 range. It registered the same mileage when David Corbin acquired it from Harvath at an unknown time. Although the mileage remained extremely low, Corbin found it needed to be painted and re-upholstered, and some wood in the body structure needed replacement. Aside from a few minor improvements undertaken by Anderson, the car currently appears much as it did when Corbin owned it: a fine example of an innovative but rarely seen marque in an extremely uncommon body type.

“There are three of the Model 64 eight-cylinder coupes on the registry that had a serial number and a name,” Anderson says of his car’s rarity. “There were two on the registry that just have the state and a question mark. There are probably parts cars and others out there, but there are three documented, known ones, so if I had to guess, there’s probably five out there.”

Graham leads the pack

The totally restyled and re-engineered 1932 Grahams blazed onto the scene to combat tanking sales caused by the Great Depression. According to Graham historian Michael Keller, Graham Brothers Joseph B., Robert C. and Ray A. knew by 1930 that to keep their Detroit-based car business afloat, they would have to fight hard for any slice they could get of the quickly shrunken new-car market. That meant designing and engineering an innovative, all-new car that represented an excellent value.

For the new 1932 model, Graham Chief Engineer Louis Thoms developed a new “Deep Banjo Frame” that gave Grahams a lower center of gravity by running the rear axle through a flat-topped frame with just a minor kick-up over the openings for the rear axle. Being flatter, the frame was also stronger, and combined with the rear axle being located within the frame rails, it allowed the Graham body to be mounted lower. Additionally, the chassis springs were placed outboard of the chassis for a wider wheel tread, further giving the slinky Blue Streak a lower center of gravity. Graham ran with it, advertising “this car is wider than it is high.” Since its low-slung stance and wider-spaced springs made the Graham an unusually good-handling car for the time, Graham also advertised the safety of the Blue Streak, which now incorporated safety glass as an additional security measure.

Graham also addressed the power of its cars. Since re-entering the car-building business by buying the failing Paige-Detroit Motor Car Co. in 1927, Graham-Paige Motors Corp. (just “Graham” by 1930) offered six- and eight-cylinder engines. For 1931, Graham had developed a new eight-cylinder engine of 245.4 cubic inches, but saw a need to make it more reliable and powerful for 1932. With resources limited, it tweaked this existing powerplant by improving its construction and internal components. Most notably and visibly, this eight-cylinder was now topped with an aluminum cylinder head instead of a cast-iron head. That allowed higher compression and a bump up to 90 hp. Graham christened its revised eight-cylinder the Blue Streak, and adapted the name to the six-cylinder models that followed in mid 1932. The Graham six-cylinder was likewise given an aluminum cylinder head for increased streak.

Backing all Graham engines was a new Synchro-Silent three-speed transmission, with synchronized second and third gears, and dash-controlled free wheeling, plus Super-Hydraulic Brakes at all four wheels.

Topping all of these performance and safety improvements were racy new Murray Corp. bodies designed for Graham by a team led by famed automobile stylist Amos E. Northup. The team included equally talented stylist Raymond Dietrich, who worked on details of the new 1932 Graham bodies. Northup’s team designed streamlined bodies that leapt into the immediate future with smoother edges; a raked-back windshield; a sloped back grille; skirted fenders; painted headlamp housings nestled between the fenders and grille; a hidden radiator and radiator cap; and a thin grille. To put an exclamation mark on its stylishly modern streamlined body, Graham introduced “pearl essence” paint finishes using fish scales suspended in lacquer for an iridescent effect. Graham was the first mass producer of automobiles to offer this paint type on its automobile bodies.

With a swift-looking exterior and a stable chassis packing 90 hp, the Graham Eight looked every letter of its Blue Streak name. It was a good value, too, costing $785 for a six-cylinder coupe to as much as $1,225 for the top Deluxe Eight coupe — about the price of an entry-priced Buick coupe (Graham dropped these introductory prices by $200 by late 1932). The range of Graham introductory prices was about twice as much as that of a 1932 Ford or Chevy coupe, but one could argue the bigger Graham was about twice the car with its greater size and more substantial innovations.

While the 1932 Graham’s styling was thoroughly copied throughout the industry for 1933 and beyond, sales dropped from 1931’s total of 20,428 to 12,967 for 1932 — one of the worst years for the Great Depression. By 1934, the year supercharging became available on the Blue Streak Eight, sales had picked up to 15,745 Grahams of all types. Unlike some automotive streamlining efforts that followed in the mid 1930s (notably the Chrysler Airflow), the sleek Northup styling of the 1932 Graham was praised, so the country’s economic condition rather than the car’s styling is likely to blame for its sales dip. Also, many independent makes were slipping into oblivion, so car buyers were often hesitant to take a chance on an independent, because if the car maker were to go out of business, vehicle service and repairs could become a nightmare. Even though Anderson’s 1933 Graham Blue Streak eight is one of the most low-mileage examples known to the Graham Owners Club International, Anderson is keenly aware of how repairs can turn into a nightmare on an orphan.

Improving on perfection

“Grahams are hard to find parts for, so people get creative,” Anderson says. When he bought his 1933 Blue Streak coupe in 2017, it looked the part of the low-mileage car that it was. However, it was still an 85-year-old car that had received some changes in its eight decades, mostly by James Rohen. Anderson immediately set to work reversing the changes to make it more authentic. Since the Graham had been parked for several years, he also had work ahead of him to make it drivable.

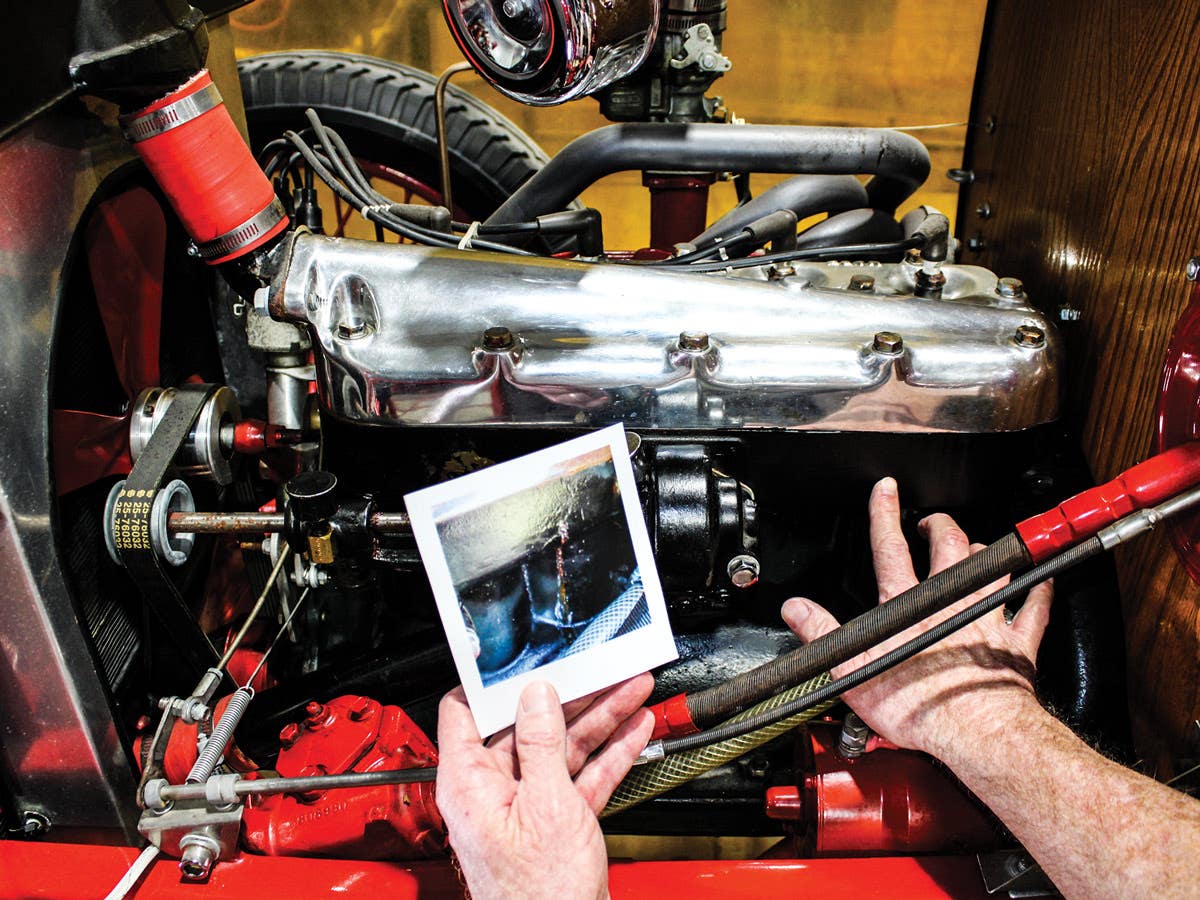

“When I got the car, the headlights were earlier. They were square body style — 1928 to ’31 — so I put a set of original headlights on it. It had a wrong door handle, so I fixed little stuff like that. The big thing I did to it was I completely rebuilt the engine.”

Rebuilding the Graham’s engine is arguably a bigger task than on other 1933 cars, because some engine parts haven’t been available since the 1930s. “The original engine, David Corbin had the thing rebuilt, and that is what his son-in-law told me, and when I tore the engine apart, I could see that it had been freshly rebuilt,” Anderson said. “It had very low mileage, but there were several things not right and I had to rebuild the engine.

“The tolerances were tighter than heck, but whoever did the babbit bearings didn’t know what they were doing,” he noted. “There were chunks of babbit missing.

“What got me taking the engine apart was a valve head snapped off and I had zero compression in one cylinder. I noticed two of the cam bearings had slid out of place and were rattling around the camshaft. It was just obvious this engine needed to come apart.

“The interesting thing is I was really concerned about the cam bearings. They haven’t made the cam bearings for this car since the car was new. People machine new cam bearings, but I don’t know if anyone knows what the original press fit was for those. I spent hours with bearing catalogs trying to find something I could make work. Lo and behind, I found a cam bearing out of a Mack truck semi that had a larger outside diameter and smaller inside diameter so we could machine out the block to fit this bearing, and grind the cam bearings to allow the machine shop to machine the cam journals smaller. We found a way to get modern cam bearings out of a 11-liter Mack semi engine. The old camshafts had giant-size journal bearings, so modern car bearings are too small.”

With the engine freshly rebuilt, the Graham is ready to run again, although Anderson admits it doesn’t get out as much as he’d like.

“I drive it once a year, maybe 15-20 miles,” he says. “I have too many cars and they don’t get enough attention.”

In addition to the featured 1933 coupe and the supercharged 1934 sedan that started his Graham fandom, Anderson has a 1934 Blue Streak Eight convertible coupe and a supercharged 1935 Blue Streak sedan. He’s content that none of them are concours-ready, even if he doesn’t get to drive them enough — including the coupe he waited so long to land.

“I live on a gravel road, I have four miles of gravel before I get to pavement, so I have no intention of going after any awards with the car. I just want to make sure I maintain it and love it.”

SHOW US YOUR WHEELS!

If you’ve got an old car you love, we want to hear about it. Email us at oldcars@aimmedia.com

If you like stories like these and other classic car features, check out Old Cars magazine. CLICK HERE to subscribe.

Want a taste of Old Cars magazine first? Sign up for our weekly e-newsletter and get a FREE complimentary digital issue download of our print magazine.

Angelo Van Bogart is the editor of Old Cars magazine and wrote the column "Hot Wheels Hunting" for Toy Cars & Models magazine for several years. He has authored several books including "Hot Wheels 40 Years," "Hot Wheels Classics: The Redline Era" and "Cadillac: 100 Years of Innovation." His 2023 book "Inside the Duesenberg SSJ" is his latest. He can be reached at avanbogart@aimmedia.com