In this column, I have the honor of introducing my Undiscovered Classics partner, Mike Puma, who is writing his first “Undiscovered Classics” column. Mike and I became friends in the early 2020s when he purchased the very car that he is writing about today. He continues to be a critical part of what we do in saving handcrafted cars, including researching and sharing that history. One of his most notable contributions has been the expansion of our social media channels, including our growing YouTube channel featuring “undiscovered classics” and their ongoing restorations. I’m thankful to have Mike as a partner, and I think you’ll find him a valued addition to this column’s writers. So without delay, let’s get to Mike’s first story.

Go get ’em, Mike! — Geoff Hacker, Undiscovered Classics Founder

As many classic car aficionados know, electric cars are as old as their internal-combustion cousins, which quickly surpassed them in large part to the introduction of the self-starter. Ironically, that technology was borrowed from an electric car even though Cadillac is often credited with having the first self-starter.

By the 1920s, the electric car was largely a thing of the past, but over the following decades, experimentation continued to improve their range, speed and reliability. They became more ubiquitous by the 1970s with the gas crisis, but the cars in that era were often very small compared to their full-size counterparts of the early 20th Century.

In the decades between, many individuals and companies tried their hand at making a full-size electric car, but most have been lost to history or modified beyond recognition, with the exception of the car that we’ll be talking about today: the 1959 LaDawri Conquest by General Electric.

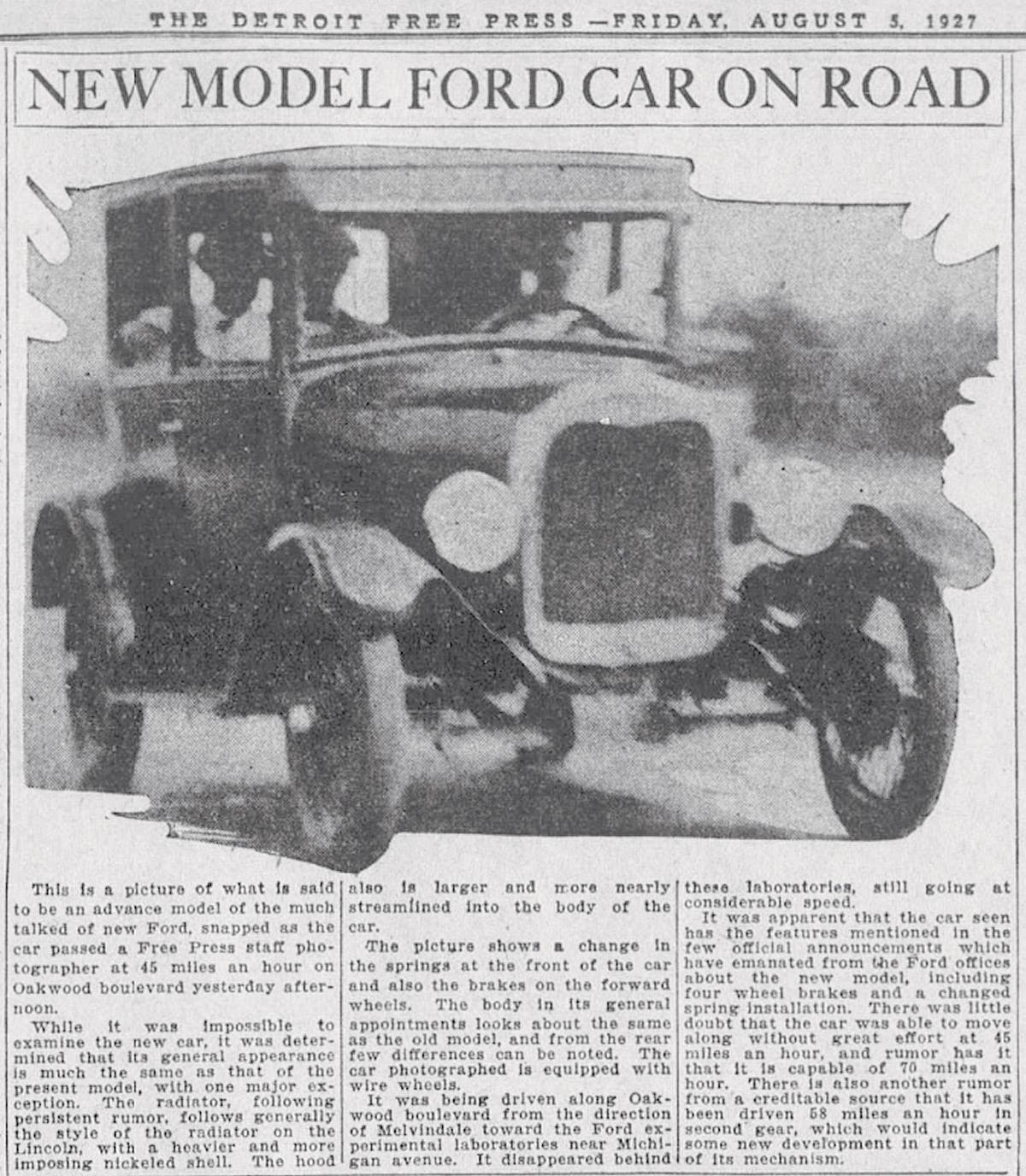

Like so many others out there looking for their next project, I found myself searching eBay for classic cars close to home. Having just turned 30 years old and growing bored with the same old production cars, I wasn’t sure what I was hoping to find. Scrolling through the usual suspects, I finally saw something I’d never seen on eBay or anywhere else: a LaDawri Conquest. It was a car so obscure that eBay didn’t even have an option for it in the auction title; it was simply listed as “1959 Other Makes,” but the photo was intriguing enough. The listing description wasn’t much more informative, just noting the make and model and a short, casual note about it being an experimental electric prototype built by General Electric.

I couldn’t reach out to Jim, the seller, fast enough. He began sending me little snippets of the car’s history, which were just the tip of the iceberg. Jim was settling the estate of his uncle, Edwin Kolatorowicz, who served as one of the main electrical engineers on the project. Edwin had an impressive resume, having studied engineering at MIT and Purdue University and had several patents in the field to his name. Jim recalled him fondly, remembering his uncle picking him up from school in the unique car and driving it around their hometown of Erie, Pa.

We formed a good rapport over the course of the auction, and I hoped to be the next steward of the car and its unique history. Unfortunately, I wasn’t quick enough at the end of the auction and lost out. A bit devastated, I reached back out to Jim and wished him luck with the sale, but let him know that if the buyer backed out, I’d be waiting in the wings.

Just about a month later, the buyer had completely disappeared, and I had my shot at redemption! As it turned out, the buyer had planned to gut the entire drivetrain and put the body on a Corvette chassis. If that came to pass, it would have destroyed what we now know to be the single-most intact, postwar electric hybrid in America.

The LaDawri had been stuffed into the garage at Edwin’s home since at least 1962, and a half-century of stuff had been piled around and on top of it, making it barely visible. Anyone who has an engineer in their family or as a friend knows one consistent thing amongst nearly all of them; they can be real pack rats, which isn’t always a bad thing.

After the family cleared a path to the car and had it pulled out, it was time for a long overdue bath. Unbeknownst to them, Uncle Ed had wisely put all the documents about the construction of the car and drivetrain in the passenger footwell. That was a saving grace, as they almost certainly wouldn’t have been found otherwise.

The extent of the documentation was far more than I could have hoped: departmental correspondence about the project progress, drawings, diagrams, component manuals and a few historic photos. Most notably, there was a file an inch thick that chronicled the build from start to finish, which was sent to their internal patent attorney at GE for consideration.

GE began the experiment at its DC Locomotive plant in Erie, Pa., around late 1957. The choice of the LaDawri Conquest to serve as the test mule for its system isn’t entirely known, but there are a few clues. Based on the documentation and Jim’s recollections of his uncle’s stories, GE was considering mass production of its own electric car. The company wanted a car that was lightweight and could serve as a second household car for shorter “around town” trips.

In 1961, after a visit from the president of GE to see the completed car, the project was shuttered, having been deemed too expensive to competitively bring to market. Edwin made his bid to purchase the car, likely saving it from destruction. He was able to bring it home for his personal use.

The body and mechanicals

LaDawri Coachcraft was one of many bespoke sports car companies producing uniquely designed sports cars and fiberglass bodies for people who wanted to build their own sports car. The Conquest was the first model designed (1956) and was offered by Les Dawes, who ran the business with his wife, Joan. They quickly expanded their range of offerings to many other models and later acquired several other sports car body companies, such as Victress. The depth of their offerings made them the largest company in the era before they called it quits in the mid 1960s.

Joan is still with us today, and while she didn’t recall this specific car, letters that came with the car indicated that Les knew about the project. There wasn’t a letter with the files from GE explaining the project to Les, but we do have a response he sent them asking for “full information on the project as it progresses,” which must have been exciting for him to see such a unique drivetrain envisioned for his car.

A few different iterations were being considered for the drivetrain, including the potential for dual motors at the rear and a unique fuel cell that would be used for recharging the batteries. After evaluating several different battery options, it became clear that nothing was going to be fully up to the task for a standalone electric system.

Instead, the team took a new approach for a hybrid design. The propulsion would still be entirely electric, but onboard recharging would be gas powered. They used almost entirely off-the-shelf parts from GE, and every component used had the product spec kept with the documentation.

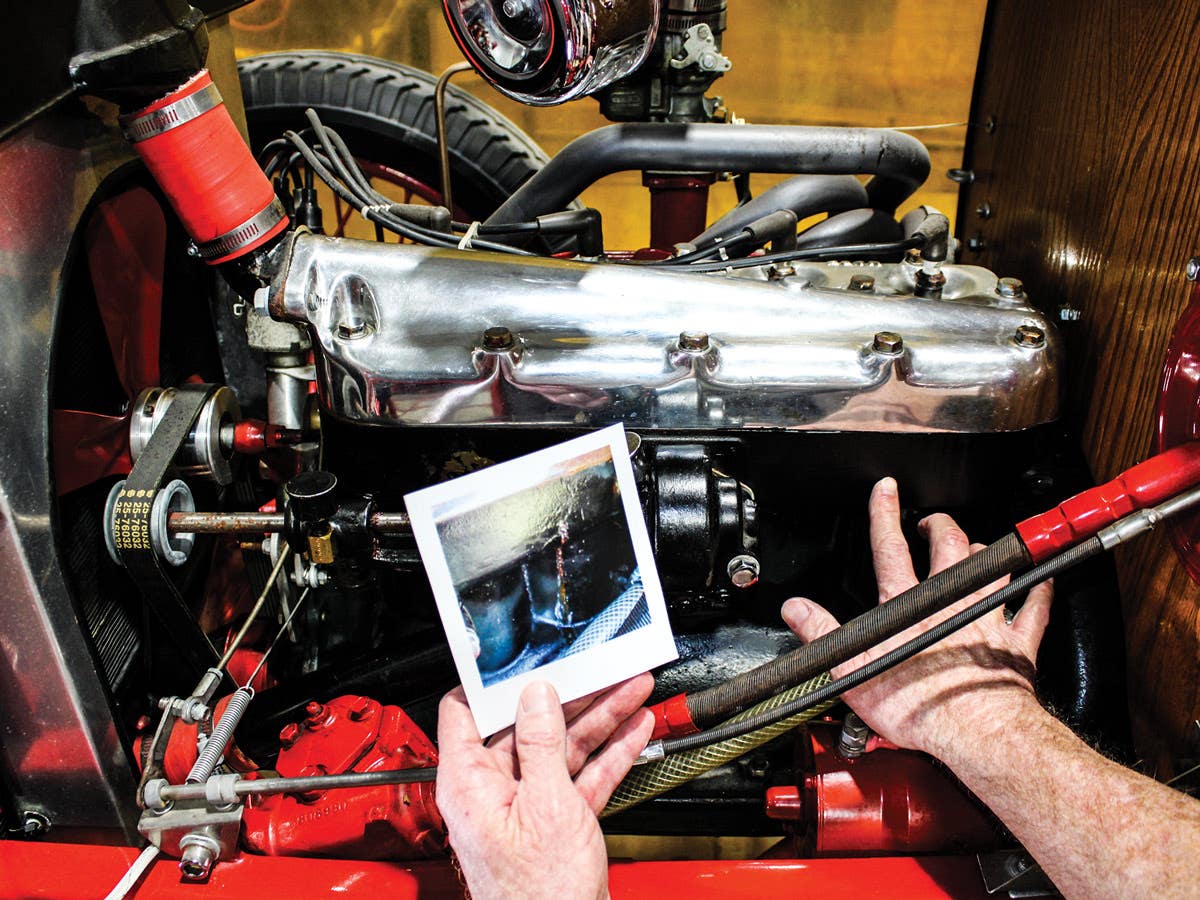

Ultimately, the system had half a ton of lead-acid batteries under the hood with the complete drivetrain in the rear. The battery power passed through a massive generator, which sat behind the passenger compartment, sending power to the Truck-O-Dyne electric traction motor and propelling the car. Mounted to the backside of the seat, within the rear engine compartment, was a massive switchboard of relays, fuses and wires acting as the brain of the system.

When it came to the on-board recharging, the generator was tied to a custom 5.75-hp Briggs & Stratton gas engine by a clutch pack with three phenolic discs. The output shaft from the generator to the gas engine spins freely until energized, which compresses the phenolic discs and enables the generator to start the gas engine. Once running, the clutch pack is disengaged, allowing the engine to spin the generator at a set rpm for the onboard recharging.

‘Jump starting’ an old electric

Once the car was home and I started poring over the documents, it was clear I was in over my head if I hoped to get the car back on the road. There were no notes about why the car had been parked for so long, the electric drive motor was full of nuts from squirrels and the batteries were long gone.

Enter the real hero of the story, my friend and automotive expert, George Dellapenta. George had worked through some electrical gremlins on my other cars and was thrilled at the opportunity — once he had a chance to see the car. His passion for it was equally matched to my own and he was willing to take it on, the caveat being that we may not be successful as there certainly was no shop manual to go by here.

After about a year, George had worked his magic and gone through every component of the car to ensure success. He was meticulous in his repairs and barely had to replace a wire or two along the way, keeping it as intact as possible.

Since GE shuttered the program, likely considering it a failure, there was no press about the car and it never received its place in electric car history. But that is changing. The systems are fully operational, thanks to George’s hard work, and it can operate under its own power for the first time in half a century.

This hybrid-electric car by GE is special in many ways, but one of the most interesting is based on the size of the car. Virtually all postwar electric cars of the ’40s and ’50s were small cars — microcars, or shopping cart-sized cars — not full-size cars, or at least as large as an American sports car. The GE LaDawri Conquest is about the size of a Corvette. We’ve only identified five large fiberglass-bodied cars of this size or near this size that were built and shown in the immediate postwar years. These fiberglass-bodied electric cars and hybrids include:

1953 Glasspar Moto or Banning Special

1955 LaSaetta “Electronic”

1956 Victress Pioneer

1958 Alken Nik-L-Silver Special

1959 GE LaDawri (car in this story)

1960 Nu Klea (owned by Jeff Lane)

1962 Voltra

Except for the LaDawri, most of the cars on the list above are lost to time or are so modified with the removal of their electric systems that they may not be recognizable. Now that this GE LaDawri Conquest is operational and its history is known and ready to share, we’re looking for our first public display of this intriguing car. Are there any museum curators interested in helping celebrate this car? Think of it as a long, lost early postwar relative to the electric cars that are becoming so popular today. We think it could be fun for the museum and public alike.

If you like stories like these and other classic car features, check out Old Cars magazine. CLICK HERE to subscribe.

Want a taste of Old Cars magazine first? Sign up for our weekly e-newsletter and get a FREE complimentary digital issue download of our print magazine.