Boogie with the Electrics

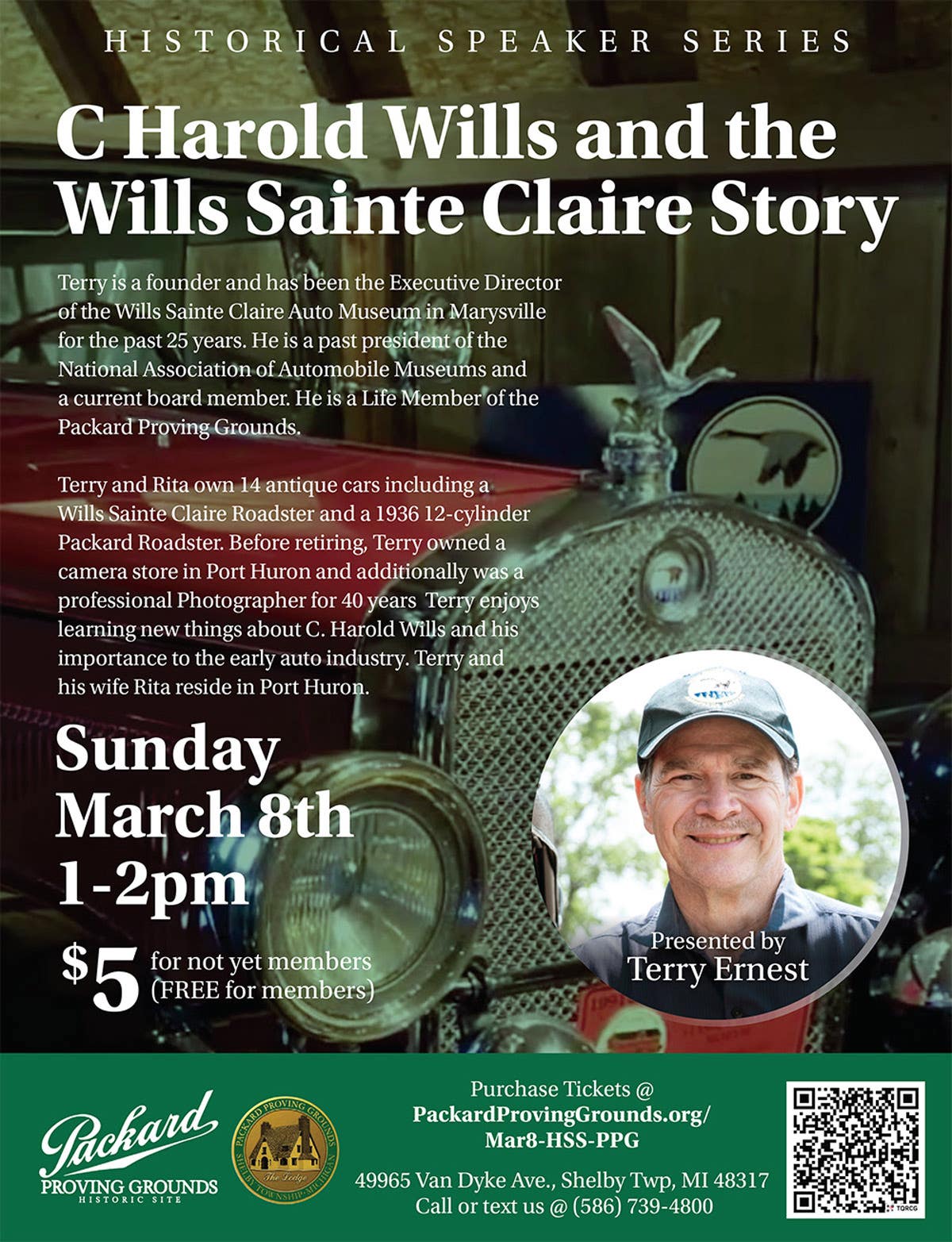

Although not the only electric manufacturer, Rauch and Lang gained a noticeable slice of the electric car business by 1914 .

If you had your choice a century ago, would you have preferred a gasoline-powered car, a steamer or one that ran on electricity? It was a toss-up as to which motive power would dominate the car industry back in the days when $5 was a very nice daily wage and home-entertainment systems — even radio itself — were yet to be invented or were commercially feasible. Honestly, home entertainment boiled down to privately reading a book, engaging checkers with your family and friends or playing catch with your black-and-white dog named Checkers.

In the 21st Century, electric-powered cars are returning to vogue. Hybrids led the way, and the Tesla brand has received immense attention, although Croatian Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) was not the inventor of it. Still, the application of his name is well deserved out of respect for the electrical genius he professed.

A name that gained a noticeable slice of the electric car business by 1914 was Rauch & Lang. It was not to be alone in that field. The likes of Columbia, Baker, Waverly and even attempts by investor Thomas Edison egged on the business ventures. Electric power was clean (although at times sulfuric smelling), would not seem as dangerous as a steam-car boiler (yes, there were rare instances when explosions occurred) and needn’t be as speedy as gasoline-powered internal-engine cars that, too often, went far too fast for the rudimentary roads of that era, errantly straying from the path and crashing into house, barn, wagon, buggy, tree or constable whose vain effort to halt the vehicle were met with injury.

Usually, it took a half hour, at best, to fire up a head of steam for a steamer in those days. Generally, a gasoline car took hand cranking to get it started. The person doing the job was risking healthy limbs since backfires and kickbacks of the steel crank could readily inflict a bone-breaking smash or at least a welting bruise to hand, arm — even leg or ankle. Safest and easiest of the modes was the electric car. If the batteries were charged and in working condition, the car’s controls took a few motions by the driver (often called “operator”) before the motive carriage was on its merry way.

Granted, the charge of the batteries and weather limited the range of travel, and round trips had to be measured and planned. Charging stations were plotted for longer trips. Of course, with multiple batteries, there was a risk of one conking out with hardly a sputter, which brought the stately electric carriage to an abrupt halt. There were times when mistaken calculations put the vehicle to the side of the road with nary a sign of spark. OK, so drivers (even riders) took to walking, which was just as healthy to do back then as it is today. Truth be known, the owners and riders in just about every car made before 1914 had to wisely wear walking shoes, for even the best of “machines” stopped dead in their tracks now and then, when it was mostly unexpected.

All that aside, how good was the Rauch & Lang? The applied name started with Bavarian Jacob J. Rauch, who settled in Ohio as a blacksmith. In 1863, he died at Gettysburg and son Charles kept the creative fire burning by specializing in carriage building. Wealthy Charles E.J. Lang, of the German von Lang family, coupled with the venture and more fancy carriages resulted. Eventually, 1905 was the blast-off year for the electric Rauch & Lang, with production resulting in at least four dozen self-powered carriages. By 1908, production was up to 500 for the year. Back orders were for more than half that number. Business looked very good and continued to do well. The car was very popular in San Francisco, a stylish city with more than a few hills that the car could master.

The Rauch & Lang was expensive at more than $3,000 each in some of those early years. Truly, in the eyes of the public, owning an automobile was tantamount to being wealthy. The style and workmanship was “old school” in quality. Heads turned when the electric eased along. In 1915, there was a merge with the Baker electric folks. Financial backing by General Electric soon followed in a joint venture leading to the Owen Magnetic, a car well worth a future article.

By the time of the Great Depression, the company operation was better known as Raulang and concentrated on special carriage work for automobiles and eventually leaned toward service vehicles and “woodies.”

How “hobby pleasant” is an old electric car today? Owners enjoy the casual speed on lesser roadways in cities and on state roads between towns. Forget highway travel due to the greater legal minimum speeds and due to the gawking of drivers that make “old car driving” dangerous at times. Electric cars gain more attention than other contemporary gas-powered cars due to the upright, high-hat silhouette that was claimed by most electrics. Replacing a regiment of batteries can be expensive, but seems more congenial when considering the non-payment of heavily taxed gasoline. As on most other cars, there is maintenance when it comes to chassis lubrication, and you must give attention to the working parts and electrical wiring that prevails in making the electric “different.”

Most people like the old car hobby because of the difference of owning a piece of history that still motors along in parades and on tours, so being different is OK. It’s a matter of choice as to how different a car owner wishes to appear. As to values, some folks may speculate that, with the rise in interest on new electric cars, that old ones will gain in value. That’s a “perhaps” that is yet to be realized, so follow the adage among collectors that if you like a car, consider getting it. Don’t let future value be the final determiner.

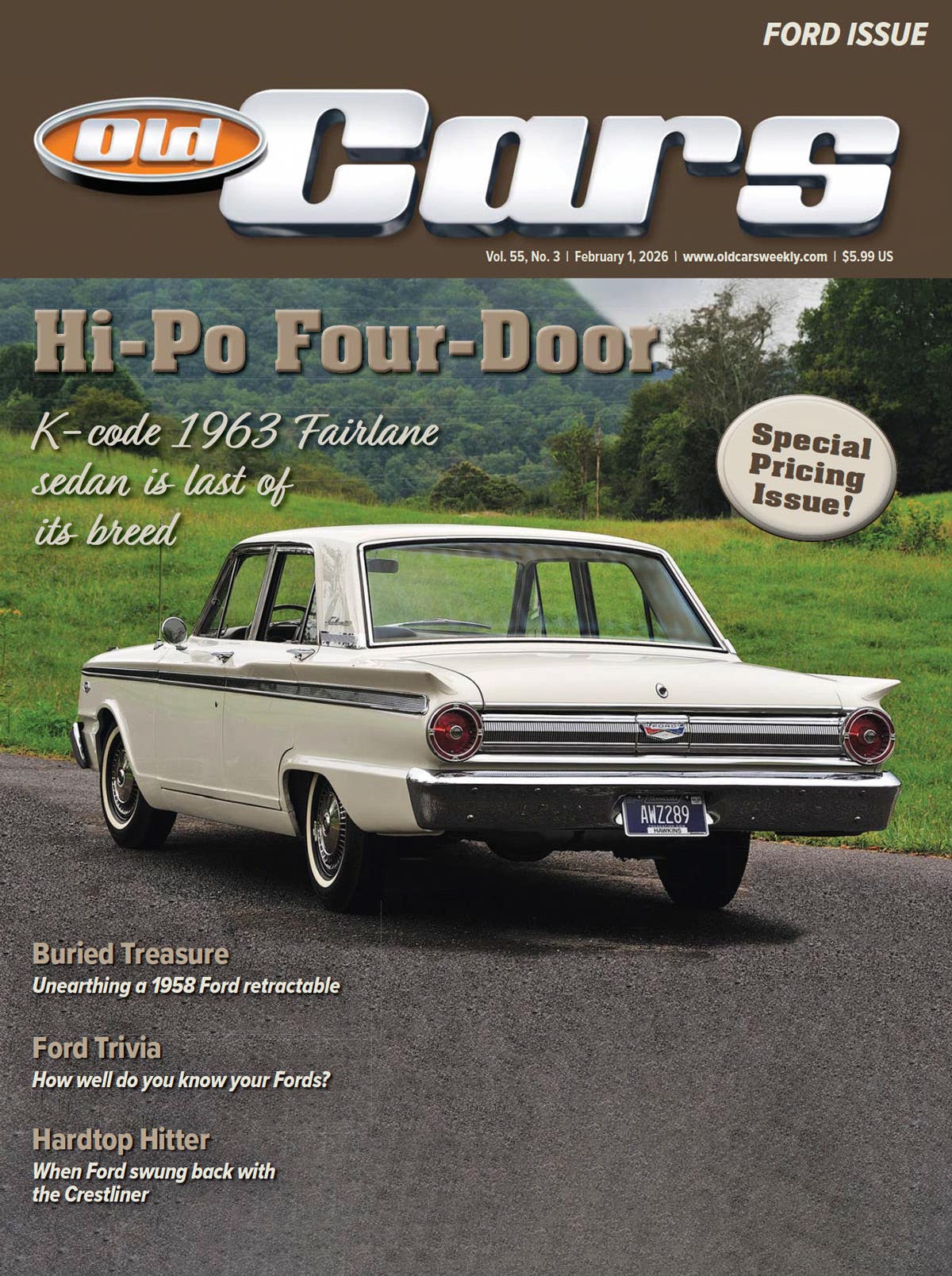

If you like stories like these and other classic car features, check out Old Cars magazine. CLICK HERE to subscribe.

Want a taste of Old Cars magazine first? Sign up for our weekly e-newsletter and get a FREE complimentary digital issue download of our print magazine.