(Editor's note: These great memories from Pat Olk, a former employee of Mercury Outboards, were sent to Old Cars for "Sound Your Horn." Due to the length and quality of the information, we present Mr. Olk's letter here, where it can be given proper space.)

Your story in the Jan. 18 issue about Carl Kiekhaefer and the Mercury Outboard Racing Team brought back a flood of memories.

I was 18 and fresh out of high school when I got a job at the Mercury Research Lab where the racing headquarters were located. I worked there through half of the 1955 season and all of 1956.

Like the article stated, they won just about every race they entered during this "stone age of racing."

No less than a half dozen Chrysler FirePower Hemi engines were ready to drop in one of Carl Kiekhaefer's racing Chrysler 300s. (John Gunnell collection)

In 1955, Carl raced four 1955 C-300s and one Chevrolet. The Chevrolet was built for one race just to show the factory team that Kiekhaefer could compete with them and beat them. After one winning race, the car was converted back into a company car. The four C-300s were raced in NASCAR and the AAA.

The picture of Kiekhaefer with two cars and drivers Tim Flock and Frank Mundy was especially memorable. The picture was taken at the Oshkosh, Wis., airport using the Kimberly-Clark hangar wall for background. The Mercury Marine hangar was next to it, but Kimberly-Clark's white wall made for a better background.

Kiekhaefer had called the research lab that day because there were some trophies left behind in his office and he wanted them for that picture. He said, "I can get to and from the airport in eight minutes and I expect those trophies here in that time." I rushed the trophies to the airport in a 1955 Chrysler station wagon with a retired 300 racing engine in it. Traffic wasn't as heavy in those days and at one point on Highway 41, I hit 122 mph. The trophies arrived safe and sound in time. Kiekhaefer was happy, and I stayed to watch the photo session.

Kiekhaefer made quite a showing when he arrived in this convoy of trucks advertising his Mercury outboards and carrying 300s. Tim Flock drove the Chrysler C-300, car No. 300, pictured at the rear of the convoy, and the tank hanging under the truck carrying his car reads, "Flock Juice." (John Gunnell collection)

Kiekhaefer was an extremely intelligent and clever engineer and brought racing into the 20th century. He made many changes in his cars which, at the time, were revolutionary. He had the least amount of bends in the exhaust system of his cars, hence, the knock-out plates under the trunk lid for through-the-trunk exhaust."

Once, while calibrating a '56 Ford engine, he got the idea that longer, straighter exhaust pipes would increase the horsepower. He had his maintenance department knock two concrete blocks out of back wall of the dynamometer room and extend the four-inch pipes out the holes in the wall. The noise reverberated off the steel building 75 feet beyond; it was so loud that the neighbors called the police, who descended on the research lab.

The 1955 Chrysler had two four-inch pipes and the 1956s had four three-inch pipes.

With his dynamometer, Kiekhaefer could break in a new engine and then test it for horsepower. Supposedly, a new 300 engine could only pull about 275 hp. Each of his engines was torn down, rebuilt, honed a secret way, broke in for eight hours on the dynamometer and then calibrated for horsepower.

When a new engine had to be broken in on the dynamometer, it would be done from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. Two people would stay the night behind the plate glass, operate the counsel and watch the engine The speed was increased by 500 rpm every two hours. The day crew could then begin calibrating. The engines would be anywhere from 340 to 365 hp when he was done with them. Then, they would be rated, crated and ready for installation.

Odd as it may seem, the Imperial limousine behind the Daytona Beach Flying Mile-winning Chrysler is relatively important to the history of Kiekhaefer's success: Kiekhaefer had racing tires broke in on the Imperial by driving each set of tires 500 miles before putting them on a race car. (John Gunnell collection)

Kiekhaefer was a fanatic about tires. I think that, up to that time, nobody thought of wide rims. He would cut rims and weld the two wider portions together. The tires were never raced until they had 500 miles on them. To do this, his personal New Yorker and Imperial and other company cars all had racing tires on them. Office personnel would spend their days driving around, putting miles on the tires. After dismounting the tires, Kiekhaefer would personally examine them. Then, they would be balanced and stockpiled for racing. In those days, there were both dirt and asphalt tracks so there were different tires.

One of the ways he intimidated other racing teams was by showing up in the fancy Ford cab-over trucks painted red, white and blue; the cars were all painted white. He had four or five white-uniformed crew members for each car. In those days, cars were driven to the track or towed with a tow bar. There were no trucks or trailers. It was quite a jaw-dropping sight to see his team pull in. To further intimidate, he had stacks and stacks of tires crammed into every space there was in the truck and car. The beautiful leather headliner and side panels were all scuffed black from those tires.

In 1956, he acquired four new Chrysler 300-Bs, two Dodge D-500s and one Dodge D-500 convertible to compete in the new 1956 mid-year convertible circuit with Frank Mundy driving. He also acquired a 1956 Ford, which is a story in itself.

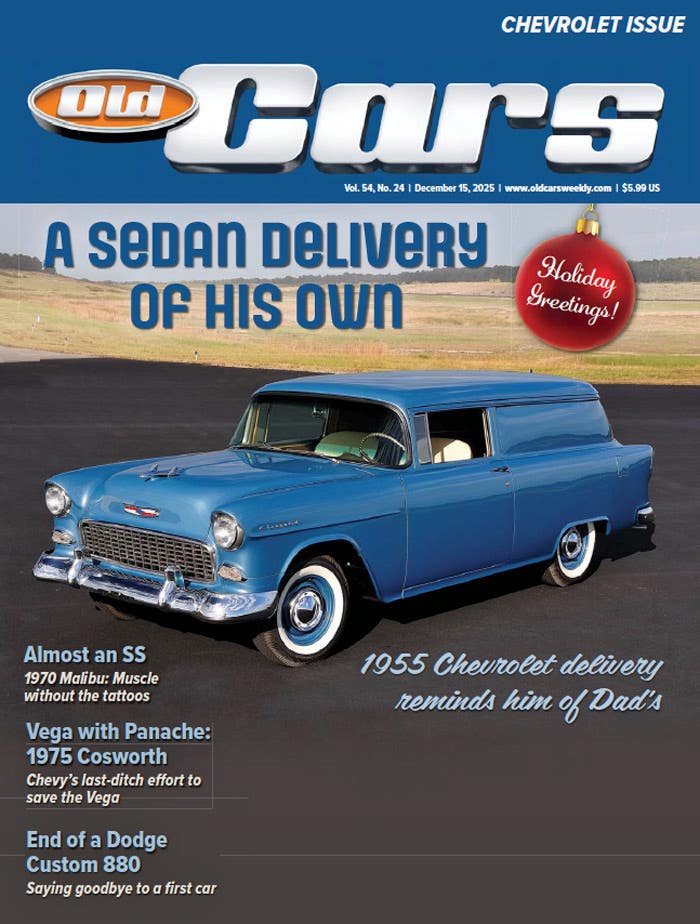

Kiekhaefer raced four Chrysler C-300s and a 1955 Chevrolet in 1955. The Chevrolet is pictured here, and after it won the single race in which it was entered, Kiekhaefer had it converted to a company car. Where did it end up? (John Gunnell collection)

In 1956, AAA disbanded to be replaced by USAC. I think Kiekhaefer just raced NASCAR that year. In 1956, the Ford factory teams were starting to have some success, and Kiekhaefer decided to beat them at their own game. He acquired a "plain Jane" 1956 Mainliner two-door and made a race car out of it. He intended to use it only once, and had a local body shop send out a body man to remove the cloth headliner, to be replaced later.

Ford had a new engine that it was using, and when Kiekhaefer tried to get one, the local Ford dealer told him they didn't exist and weren't listed in the parts book. In those days, if anything was used for racing, it had to be in the parts book and at least 2,000 had to be available for purchase by the general public. "Strictly stock" had to be what was used in race cars, as well as what grandma drove to church on Sunday. It didn't take long for Kiekhaefer to get on the phone to Bill France and any other "powers that be," and he got his parts. He raced once, won and converted the "plain Jane" Ford back again.

Because Kiekhaefer was so successful and always pushing the limit, there seemed to be pending legislation aimed at counteracting his success. Many times, I'd walk by his open office door and hear him jawing at Bill France. He usually always got his way.

As the end of the week approached and race day neared, getting the cars ready became top priority. Employees might punch in at 7 a.m. and still be there the next day at 7 a.m. Kiekhaefer would be right there in his white coveralls working along with everyone else. He had f ood and refreshments catered in.

Compared to today, in 1955 and 1956, the police were pretty lax. When there was a AAA race at the Milwaukee Mile, the crew would go on Saturday to practice. Instead of trucking the cars down from Osh-kosh, they would drive them. They had no mufflers, lights, etc., and would drive right down Highway 41. In Oshkosh, the last thing that was done to a car before race time was to get it aligned. There was a body shop on the other side of town whose owner was trusted by Kiekhaefer to do all of the alignments. He was always on call. An alignment at that time was $7.50 during business hours and $10 any other time. It could be any time of night or early morning when a car would be ready. They would call the body shop owner and he would be waiting at the shop. The cars would be driven to the shop, again with no mufflers or lights, right through town with a company vehicle in the front and one in the back.

In January 1956, Kiekhaefer acquired a maroon 1956 300-B to race in the Daytona Flying Mile. This was before radar, so to test the speed, they made a speed check unit using two hoses so many feet apart. It was similar to what police used in those days. The research plant was situated on an approximate two-mile stretch of road on the northern Oshkosh city limits. One Saturday afternoon, the hoses were set up in front of the building and spotters were placed at each end of the road. When the traffic was clear, the spotters would signal and the car would take off from one end of the road, accelerating as hard and fast as it could reaching speeds over 100 mph as it passed the facility. All this on a city street!

In the fall of 1956, I was hired at a different and better job. I had been a flunky, sweeper and parts chaser with no future at Mercury Marine.

My last day on the job was a Thursday. There was a lot of pre-race activity that week, and lots of night overtime work. Being my last week, I clocked out at 4:30 every day and didn't come back to work at night. That noon, I was by the wash fountain cleaning up for lunch when old man Kiekhaefer spotted me. Unbeknownst to him, this was my last day. He said, "I haven't seen you here at night all week. We have a lot of work to do and I want to see you here tonight. You young guys... all you want to do at night is go out and drink beer!" Needless to say, I clocked out at 4:30 and never looked back. I think I went out and drank beer that night, too!